Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: An Off-Balance Retrospective.

In a world without gold, we might have been heroes.

Table of Contents

It is the rare creative undertaking that is totally linear, all the way through.

And perhaps no franchise in gaming has best exemplified this over its first few years quite like Ubisoft’s Assassin’s Creed - even as its core framework was quickly nailed down, each title brought something of its own to the table.

Be it mechanical and narrative tweaks or a broader sense of experimentation as it blended genres and differing gameplay styles with abandon.

Bulletproof?

Of course not.

Repetition and complacency were noted criticisms, even within the midst of critical success in the early 2010s, as the series continually reoriented itself around ever-expanding lore, shifting audience expectations and cultural goalposts.

But with 2013’s Black Flag, it was to see those broader strokes be fully realized in a way that was then (and remains) an unquestionable high water mark for the series.

Marketed as the fourth mainline title, it was, in actuality, the sixth in release order. Primarily developed by Ubisoft Montréal, it was a prequel in some respects, a sequel in others and the first game to truly move beyond the established formula. Spotlighting the Assassin-Templar conflict from an outsider’s perspective, taking incredibly bold, assured swings in its primary gameplay loops or presenting a mostly standalone Golden Age of Piracy tale that, a decade-plus on, is not just one of the best in the long-running franchise but pirate fiction as a whole.

So, in the lead-up to the release of Assassin’s Creed Shadows later this month?

Here is Black Flag, twelve years later.

Intro (Black Flag)

Having forever believed he is destined for greatness beyond his modest means, young Welshman Edward Kenway (Matt Ryan) bids goodbye to his heartbroken wife Caroline (Luisa Guerreiro) and sets sail for the West Indies, determined to make his fortune as a privateer.

Come 1715 however, with the abrupt end of War of the Spanish Succession, once optimistic sailors have turned to piracy en masse, with Edward amongst their number.

Concurrently, he comes to count himself as a leader of a pirate collation in Nassau, where alongside his quartermasters Adéwalé (Tristan D. Lalla) and Anne Bonny (Sarah Greene), close friend Mary Read (Olivia Morgan) and infamous mentors, Ben Hornigold (Ed Stoppard), Edward “Blackbeard” Thatch (Mark Bonnar) and Charles Vane (Ralph Ineson), Edward dreams of a self-made republic, far from the reaches of King and Country.

Though when he is waylaid in a shipwreck off the Cuban coast, Edward inadvertently steps into a larger world.

After killing a rogue Assassin and then unknowingly selling trade secrets to the Templars, he finds himself at the centre of the millennia-old shadow war, as they grapple for the upper-hand throughout the Caribbean.

Yet having no use for either their philosophies or bigger-picture plans, Edward sets out to leverage both factions to his own ends as he obsessively searches for The Observatory. A First Civilization site rumoured to hold a priceless treasure with no true equal, in addition to the mysterious man who can lead him there, “The Sage”, fellow pirate Bartholomew Roberts (Oliver Milburn).

But as the years past, Edward slowly comes to realize, at great cost, that wealth alone does not a man make.

Built out from this foundation, Black Flag’s strengths are present right from its opening title card, alongside the expected series supports, starting with combat and stealth.

Combat + Stealth

In the vain of its immediate predecessors, Black Flag retains the counter/kill-chain focused combat system first introduced in Brotherhood, with an emphasis on speed, simplicity and player empowerment.

Not difficult by any reasonable metric but with no visual combo counts or overly cluttered HUD prompts, there is just a push towards consistent, unbroken momentum.

With counters, standard soldiers can be defeated in two button presses, leading into a chain, though others, such as captains or brutes, to counterbalance this, require either a defensive break or a counter-break to defeat.

Brutes, axe-wielders, can decimate the player’s health in just a few swings if treated carelessly, requiring an auto-dodge via a counter press before moving in for a break. Additionally, able to toss grenades, they add a small amount of variation to each encounter, even if it simply means changing Edward’s positioning so that his enemies absorb the impact instead. The human shield mechanic returns as well, giving the player a small window of opportunity, if surrounded by snipers, to work their way out of a jam without taking damage if a gap can’t be closed or they’re operating on ground level.

And though double counters aren’t too common, they’re fun to pull off, if one is able to work any one arena in their favour, Edward, shown to be a talented, confident combatant both armed and unarmed. By default, he duel-wields two swords and upon acquiring them, he takes to the Brotherhood’s signature weapon, dual Hidden Blades, with great skill (able to use them without limitations in open combat, in addition to stealth, as was series custom from II to Rogue). Disarming enemies can add a little change as well, with lone swords, muskets and axes all available, even if for only single use per an encounter.

Similarly, through they’re only unlocked right at the nigh-end of the story, rope darts return from Assassin’s Creed III, adding a few small wrinkles to end and post game encounters.

Through crafting, the player can eventually equip two extra holsters, allowing Edward to carry up to four flintlock pistols and pull off a chain of one-hit multi-kills as a form of mild crowd control. Generally, no, they don’t add too much (besides playing into that pirate aesthetic) but when boxed-in, be it boarding a Man-O-War or in specific story moments, they do provide an effective measure of breathing room, beyond tool-locked executions.

Sword sets are graded under three categories (speed, combo, damage), as are firearms (damage, stun, range) but besides the game’s best sets, awarded for completing all the naval and Assassin contracts, there isn’t too much incentive to consistently upgrade.

With no real difficulty curve, outside of incrementally quicker combo counts, what works, works.

Regardless, the mo-cap/stunt-work is strong, informed with particular sense of character as it relates to Edward’s combat animations. He possesses some measure of proper swordsmanship training (per the lore, through his time as a privateer and later, after being tutored by Blackbeard himself) but with a wild, rough, whatever-it-takes unpredictability, as well, befitting both his personality and chosen line of work, as a pirate.

It is a fighting style that, noticeably, contrasts well against both Haytham’s (Adrian Hough) graceful approach or Ratonhnhaké:ton/Connor’s (Noah Watts) more precise brutality in III - meanwhile, in the Freedom Cry DLC, Adéwalé, utilizing a blunderbuss and machete as his primary weapons, has his own unique animation packages, highlighting a more visceral violence the base game mostly avoids (which makes sense, given the narrative focus there).

But the on-the-ground combat in Black Flag simply does not have the same level of polish when compared to III or The Ezio Trilogy.

There is an appreciated back-and-forth when everything clicks yes but animations can often feel choppy and inconsistent. Locking, slow timing and repetition aren’t dealbreakers per se but they are present and do have bearing on the overall presentation. There is no growth, progression-wise, for either Edward, Adéwalé or the player, meaning familiarity quickly settles in.

Stealth too, suffers from this but this time around, it is very much a secondary method of problem solving.

Though not an Assassin, Edward’s personally-developed skillset closely mirrors the Brotherhood’s, retaining all the series staples up to this point. Eavesdropping, social stealth, whistling from hiding spots and tagging enemies with Eagle Vision. The biggest addition is the blowpipe, the game’s main long-range tool. Sleep and berserk darts can both incapacitate enemies to the player’s advantage and can be sequentially upgraded to increase their effectiveness, through crafting, with the proper material.

Functional but not flashy.

It does track, however, to an extent because Black Flag’s combat chips weren’t pushed in on land but rather, sea.

While III’s pure ambition wasn’t without missteps, the additions it brought the series already well-established formula were clear, though perhaps none were as impactful as the naval system.

Early on in the story, after escaping the doomed Spanish Treasure Fleet with Adéwalé’s help, Edward commanders a brig he christens the Jackdaw. Yet rather than restricting the player to siloed, scripted segments, instead, it is a core pillar of Black Flag in virtually every aspect. Exploration, storytelling and navigation thrice, in addition of course, to combat.

The tweaks made to the system, post III are immediately apparent, however: lighter, snappier and with a particular sense of fluidity, prioritizing gameplay over any broader feeling of harder realism. The player must still be mindful of wind resistance, environmental hazards and momentum, as they transition into (and out of) various sailing speeds but to a far lesser extent than the previous instalment. Bracing and reload times have been shortened too, keeping one present at all times.

Chain shot can be used to slow down, disable or sink smaller ships outright, while broadside shots, for which there are no ammo limits, are the usual go-to when surrounded by numerous enemy vessels and deal a healthy amount of damage.

Heavy shot, which is fired simply by applying trigger pressure can’t be aimed but is a step up and can decimate less well-equipped ships. Fire barrels or swivel guns can be used to follow-up (with upgrades, in rapid succession) and with a properly-upgraded ram, charge attacks are viable, as is the mortar for long-distance: creating an effective push-and-pull when wanting to hang back or needing to be more aggressive.

Designed with great purpose, it emphasizes depth in execution and active player progression.

At the onset, attacking anything beyond gunboats or schooners seems foolhardy but as one’s confidence grows, the Jackdaw is steadily upgraded and the player ventures into the more challenging areas of the map, those mostly self-imposed limitations come to fall away.

Brigs, frigates and eventually, Man-O-Wars. Each requires a slightly different tactical approach, either when engaged or boarding, especially if the player is outnumbered or battling an adversarial fort, as well. While hidden away in the far corners of the West Indies are so-dubbed “Legendary Ships”. Five in total, which push Black Flag’s ship combat (and the player’s skill) to the very limit, each, requiring particular strategy and a noted amount of patience to defeat.

Gameplay necessity superseding historical imperfections aside (for one, guns being on the top deck), it is the system Black Flag’s combat was clearly built around, even with its predecessor as a template. The end result, more than worth the initial, slow-going investment.

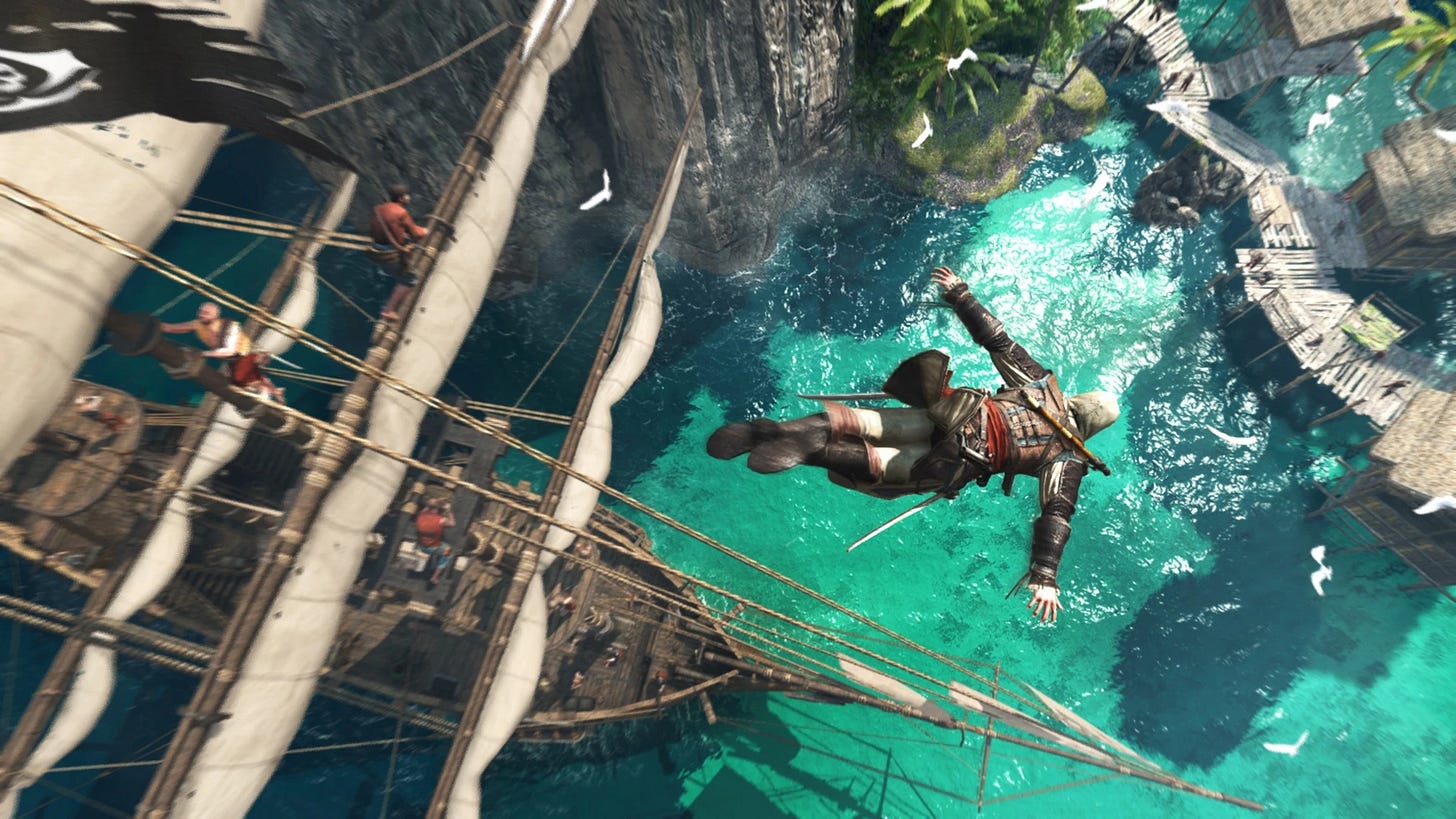

Smoke, all but filling the screen, as Edward barks orders at his crew, the thunder of a Man-O-War and the Jackdaw firing back, against crashing waves and uncertain odds.

Rouge would fine-tune and Odyssey, given its Ancient Greek setting, would take the blueprint and reinvent it but there is something that endures with the game’s naval system, even amongst the series titles that would improve upon it.

And much the same can said about Black Flag’s open world: a recreation of the 18th Century Caribbean, teeming with adventure and secrets both.

Open World + Exploration

Having all but perfected their specific version of city-based exploration come Revelations, with III, it was to see Ubisoft acknowledge that there was more to be found beyond their historical-metropolitan borders.

And while Colonial Boston and New York were good fun to traverse, the game’s lynchpin was the Frontier, a slice of the New England countryside bringing new parkour challenges - tree navigation -, a basic hunting system and a general sense of scope that was atypical for the series.

In kind, Black Flag takes the strongest elements of III’s open world and makes them the operating focus.

Most notably, the game’s deception of the West Indies, stretching from the edge of South Florida, to the Leeward Islands, are explorable nigh-seamlessly, with very little in the way of load times or interruption, while blending both rural and urban elements (with, as well, story relevant visits to North Carolina and Príncipe).

If the player sees an island or an inlet far in the distance, they can sail to it and disembark, either docking the Jackdaw or just swimming right to shore, while flowing directly into on-foot exploration. It was a noted selling point of the marketing yes but it is just so smooth, so immersive in practice, it remains a highlight of the game’s loop, unique, in the series as a whole (even up against its direct successor in Rogue, which divided its Colonial North America into three, separate maps).

Isolated fishing villages and dense jungles, crawling with no small number of English and Spanish soldiers. Long-forgotten Mayan Temples, desolate, deserted beaches or more bustling communities, dotted along various coasts.

On the city side, while Kingston and Nassau do have distinguishing atmospheres (Kingston, choked with redcoats, Nassau, for most of the story, being a pirate haven) neither stack-up to previous AC efforts (and even then, Havana, in that vain, though well-crafted, just doesn’t hold much of a candle to say, Venice or Constantinople).

And yet, each provides a series of distinctive gameplay opportunities, not unfamiliar to even more casual series players in their execution but fully immersed in the pirate fantasy Black Flag works diligently to present.

Maybe it is getting into a tavern brawl on a coastal isle as warships rage in the background. Offloading the spoils from a day of pirating, rum and sugar, in exchange for ship upgrades or to funnel money into Edward’s Bahamian homestead (this, the game’s light extension of the series’ base-building system).

Accepting an assassination contract (true to form) from a pigeon coop or scrounging for buried treasure, via stolen maps, as the sun sets.

Struggling to keep a steady hand at the helm as rapidly forming rainstorms and waterspouts threaten to drag the Jackdaw to the locker at any time, lesser ships, lost to the waves.

Raiding plantations, smuggler hideouts and underwater wrecks.

Going spearfishing for big ocean game or stalking through treetops, hunting, for crafting material. Tracking down collectibles, from sea shanties to prized armours (including one First Civilization set, naturally) or a series of mysterious letters, those, shedding some light on the inherent folly accompanying Edward’s search for The Observatory.

Practically speaking, though there may not be noticeable swings in character in the same way one might find in other AC titles, Black Flag’s Caribbean is bursting with such colour, such confidence, it is a joy to move through, either on foot or on-sea. So thick with period-heavy ambience, the humidity and sea salt spray nearly peel off the screen, a testament to those that saw it brought to life.

The art, audio and level designers, the cloth and water physics, the lighting and weather teams and so many more, a standard held up even in smaller moments.

The Jackdaw sailing, the camera pulled back with cinematic flair as the soundtrack, primarily led by composer Brian Tyler, kicks into gear, anchored by the game’s much-beloved sea shanties: a first for the series, in their visibility, that proved so popular they would return in Rogue and Odyssey both (the different time periods considered).

In a 2022 podcast feature, lead writer Darby McDevitt likened Black Flag’s shanties to something akin to “pirate radio”, a way to break up the monotony of having the player sailing, with minimal engagement, for longer stretches. Though it was a process, implementing them, that was far more complex than it would appear at first listen. Taking period appropriate texts and then reworking them, lyrically and musically as needed, to best fit everything the larger team was shooting for, while still maintaining the spirit.

Lead musician, Seán Dagher, also acknowledged the efforts put in during the recording process, an authentic verisimilitude, a top priority.

The group, layering their voices and purposely singing in a rougher style, in looking to capture that sound of untrained sailors, working the deck (a musical commitment that would be further seen, in a much more grounded way, in Freedom Cry, as spoken too by the DLC’s composer, Olivier Deriviere).

Though where Black Flag stumbles in this area? It is at something of a crossroads.

Mechanical/artistic shortcomings up against the reality of playing the title on current hardware, in which its PS3/360 origins are that much more apparent.

Be it frame rate limitations, the noticeable amounts of pop-in, stuttering or graphical dips, considering, they’re not dealbreakers.

But the weak enemy intelligence, the over reliance on tailing missions, on-foot or in the Jackdaw, the constraining nature of mission sub objectives or the generally scattered, unreliable parkour. They are very much apart of Black Flag, often to its deterrent. As for the parkour specifically, it exists as an AC hallmark of the era sure but also provokes a fair amount of frustration as Edward and Adéwalé both skitter across everything from rooftops to a ship’s rigging with no true measure of accurate player decision making: getting caught on geometry, poorly-timed jumps to incorrect responses wholesale.

Taking the good with the bad perhaps but never cleaned up, it simply exists in a state of bullying through it in tighter, more cinematically-driven story moments, even if the framework itself isn’t entirely misplaced.

Annoyances that pale in comparison to the Black Flag’s highs, however. The open world as it exists overall, next to, first and foremost, the story.

Story (Base Game + DLC)

Right from its introductory sequence, Black Flag’s storytelling promise, its belief, is evident.

Not just actively deconstructing long-standing franchise staples but the mystique surrounding its chosen historical period/people as well. The vail of piracy’s Golden Age, continually prodded at, a humanistic angle in result, often forgone in the popular space.

The base game then, overlaying two more active narrative threads with, at large, Edward’s personal journey of self-discovery is a bold move in theory, meaning any one story element could get lost in the shuffle.

But each is given space to develop in a way that feels rewarding for the scale and importance it puts forward.

In its relative infancy when the story begins, Nassau’s Pirate Republic is a place for which its now former-privateers have placed not just a good deal of their capital but broader hopes, as well, their engagement in piracy, initially presented as a means to an end. A foundation on which to build a society lacking in “traditional” English decorum yes but adhering to principles based in personal freedom.

Liberty, in its purest form, for self-made men.

It is a raw romanticism that, Black Flag’s earliest sequences (no doubt purposely) recall how the period has been generally portrayed for the better part of three hundred years: carefree, easy-going, responsibilities and governed morality, only in the service of further pleasure. This, what attracts Edward most strongly, as he strives for riches and reputation - though, in contrast to many of his allies, Blackbeard and Ben Hornigold most strongly, who sincerely believe in what they’re trying to create. But as the would-be-republic rapidly collapses, taken down by the pirates’ own mismanagement and inability to maintain anything beyond base hope, what Black Flag was clearly building towards, comes fully into view.

Dreams, scattered, as the very institutions they raged against come, unrelenting, to collect with the rope, the sword, in hand. Not buccaneers, coasting off onto the horizon but not whole criminals either. Simply, men and women who committed themselves to a cause they would have been better off cutting loose long before they did. Realization reached, in the hardest way.

It is an examination of piracy’s Golden Age that explores its seedier reality and false idealism in equal measure but as well, the dirty, dangerous, intoxicating appeal (as its gameplay loops can testify).

All contrasted with Edward’s search for the Sage, Bartholomew Roberts and through him, The Observatory.

McGuffins fundamentally but interwoven into the plot with a steadily growing clarity, that informs both the characters and the thematic edges on which they operate.

Almost entirely removed, for the majority of the narrative, from the series’ sci-fi deep cuts they’re pulling from, instead, they loosely represent a pirate treasure in the classical style. Edward and later, a handful of his Republic compatriots, determined to uncover what they believe to be a grand prize, uncaring to the chaos caused in such pursuit nor how such potential riches could be put to benefit.

Not just Nassau, as it teeters on the brink but a higher calling.

A certain Creed, perhaps.

And to that end, for some in the franchise’s fandom sphere, Black Flag’s choice to keep the direct nature of the Assassin-Templar conflict at an arm’s length for most of its runtime is what defines the weakest of its pillars, though it is within the philosophical debate that the game pulls most strongly.

Templar control, absolute in its delivery but possibly a needed antidote to the hedonistic revelry Nassau champions, while the Brotherhood pushes for their more well-realized version of freedom: that of betterment and humanitarian aid. Though at this time, in this place, their ideals can seem ill-suited. To the individual alone, they speak most strongly but in a manner of personal conviction above all.

Those nodes then, competing as they are, are left, by design, mostly free floating in the base game, steadily encircling the many of the characters but through them, the player too.

Openly challenging the black-and-white approach that defined The Ezio Trilogy but further expanding on III’s more grey area delivery, albeit, with slightly less prominence.

Though ultimately, it lands with Edward.

After chasing Bartholomew Roberts, from the Caribbean to the west coast of Africa and striking up a tenuous alliance, he finally comes to see The Observatory firsthand. A powerful First Civilization site which one can use to see through the eyes of another.

The wayward pirate, understanding, maybe too late, that his quest to seize it for personal gain has been not just misguided but caused him to be blind to the resulting consequences: the disintegration of a dream, the deaths, the abandonment of virtually all his friends.

The danger of its use for profit and control, how the Templars and Roberts, left unchecked to their scheming, would do just that.

Finding than, as Mary and Adéwalé hoped he would, solace in the Assassins and the possibility presented by their Creed. As with Anne’s assistance, he allies himself with the Brotherhood, eliminates the Templars and secures the site, vowing to continue the fight for freedom upon his return home, older and wiser both (something that was also touched upon, earlier, in the game’s major side quest chain, the Templar Hunts: which see Edward collaborating with a handful of Assassins, for both self-interest and some measure of curiosity in their mission).

Now, it isn’t free of criticism.

The structure and pacing, most notably, can be disjointed and incomplete at their worst, often leaving the player to their own devices in the open world for long stretches (which isn’t a bad thing, necessarily, given the quality of it) but then rapidly, noticeably, compressing its beats in the third act. It is a story that properly conveys its years-long length yes but just doesn’t put as much weight behind anything First Civilization related when compared to what transpires in Nassau (despite both plots, in a way, coming together) leaving the story to stutter at times, in picking that momentum back up.

Though as it stands on its own, Black Flag’s historical story is one of remarkable strength.

Presenting its thematic ideas, the minute of its world-building and laying them side-by-side, while delivering on a narrative of fantastic staying power. Mature and emotional both in its execution, particularly in its closing stanza.

But of course, in AC custom, it isn’t the whole story.

In the modern day, following Desmond’s (Nolan North) sacrifice at the end of Assassin’s Creed III, Abstergo has collected his genetic material, hoping to use the memories of his ancestors locked within in, including Edward, to further their true, Templar aims as they hunt for Pieces of Eden.

Presented in a first-person view, the player is an unnamed, physically unseen research analyst who is quickly wrapped up in conspiracy, on both sides of the Assassin-Templar war but also by way of fellow employee John Standish (Milburn, in a dual-role). A seemingly pleasant man but who is, like Bartholomew Roberts before him, a Sage: a resurrected version of the Isu Aita who is driven to bring Juno (Nadia Verrucci) back from “The Grey” whatever the cost.

Meanwhile, Shaun (Danny Wallace) and Rebecca (Eliza Schneider) have gone undercover at Abstergo, looking to undermine the Templars from the inside.

It is… well, it’s fine.

Juno’s story, as shown, would end on a cliffhanger with 2015’s Syndicate before being resolved entirely in the franchise’s auxiliary material, thereby robbing it of any real, on-screen energy. Though not just in hindsight but in the moment, with the modern day portions of Black Flag very much sectioned off from the rest (a trend that would become the status quo up until 2017’s Origins).

Yet, no longer overlaid with end-of-the-world stakes, slinking around Abstergo’s offices, unearthing lore and classified documents is fun enough, even if, yes, it doesn’t amount to anything legitimate long-term (though however much Ubisoft continues to claim that their various franchise crossovers are non-canonical, the implication alone, that a high-ranking Templar was dealt with by Watch Dogs’ protagonist Aiden Pearce himself is awesome and nothing can be said to dissuade that notion).

Elsewhere, the Aveline DLC, which sees both Noah Watts (in a voice-only capacity) and Amber Goldfarb reprise their roles as Connor and Aveline respectively, is, at the very least, a fun piece of small, semi-sequel storytelling for III and Liberation but it doesn’t have too much to present otherwise.

Instead, it is Black Flag’s main DLC episode, Freedom Cry, which takes the lead.

Set in 1735, thirteen years following the end of the base game, Freedom Cry picks up with Adéwalé, now a veteran but committed Assassin as he looks to curb emerging Templar influence in the Caribbean.

When he is shipwrecked in Port-au-Prince however, he becomes a key figure in the city’s burgeoning Maroon rebellion. Forced to confront his past as a former slave head-on, as he works to dismantle both the local slave trade and end the life of local governor, Pierre de Fayet (Marcel Jeannin), a barbaric and inhumane slave trader.

Mechanically, no, the DLC doesn’t step too far away from Black Flag’s template, which is to be expected. Ship navigation, the larger open world loop, everything returns more-or-less as is, with a few tweaks (for one, instead of recruiting pirates, Adéwalé is liberating slaves).

With two new weapon types, in the blunderbuss and machete (as mentioned previously), there is a small switch-up in combat, mildly, both in approach and in presentation, though it is the narrative maturity, once more, which is most apparent.

Nine missions, with a dash of open-world activities aside, Freedom Cry is a noticeably compact experience (enough so, that is was eventually released as a standalone title).

Adéwalé, fighting alongside his newly-found allies to assist the rebellion, while not once backing down from the reality it is looking to present, in the horrors of slavery as he brings de Fayet to a deserved end.

Though, like the best of Black Flag overall, it shines a consistently strong light on its performers (and through them, the writing team) giving each ample room to deliver.

Performances (Supporting)

In series tradition, Black Flag embraces its chosen historical period with a particular earnestness, as it relates to its large cast of fictionalized, historical figures. Although with something of an in media res approach, as it relates to their narrative placement, Black Flag bypasses the occasional struggles AC has had in honestly establishing them - to the great success, for both the writing and the performances overall.

The Golden Age of Piracy produced some of history’s most plainly enduring and colourful individuals, romanticized and idolized by some, despised by others, making it a natural playground for an Assassin’s Creed title.

Allies, on a line thin between camaraderie and antagonism.

Though for as strongly as their names and darkest exploits were itched into heavy stone, the whole accuracy of those then-contemporary sources is still widely disputed in academic circles today. For many, real names, beyond possible pseudonyms, birthplaces and ages. Personal histories both before and after their documented piratical exploits, for those who escaped the noose or indisputable deaths.

The basics, as it were. Much of it, still subject to a measure of conjecture.

But as a byproduct of this, Black Flag’s writers and performers, them, through their larger performance capture, bring an incredible amount of believable heft to their portrayals. A lived-in honesty of sorts, fictionalized though it may be, that still hews closely to those real-world benchmarks.

So as Ben Hornigold, Ed Stoppard is a man who holds his convictions proudly on his sleeve.

He believes deeply, truly, in the possibility the nascent Republic in Nassau represents and refusing to waste time on hypotheticals, he is furious to see it fall away to diseased ash. Finding his way to becoming a pirate hunter and later still, a Templar because of it. The order, the structure they promise, it is exactly what he has been looking for as he turns against his former friends and in time, comes to enter Edward’s crosshairs because of it.

Stoppard shows a noticeable understanding of his character here, particularly in the back-half of his arc. The conviction for which he speaks, pushing against the notions of both AC of old and Edward’s once unshakable beliefs, as his one-time protégé is forced to strike him down: in pursuit of grandeur he later learns (to Hornigold’s warnings) to be an utterly unfulfilling one.

With variation on this presentation is Ralph Ineson as Charles Vane, a cruel, dark-hearted man (true with what is known about him historically) who cares little for higher principle but speaks to that drive for wealth above anything else, in joining in Edward’s search.

And while there is some joviality to many of Black Flag’s supporting cast, Vane, by way of Ineson’s locked-in performance, is the polar opposite. Humourless, terribly violent, a powder keg, waiting to explode at a moment’s notice. More so, as betrayal and mutiny see him eventually descend into debilitating madness (something, funnily enough, Ineson himself joked about in press material, describing the process as “relaxing”).

Mark Bonnar, as Edward Thatch, the man who would achieve infamy in both life and death as “Blackbeard” has more historical bearing to consider and yet, Bonnar’s command is on-point from the moment he appears. An eager mentor to Edward, he has taken the younger pirate under his wing as both protégé and something of an unspoken, adopted son and strives to help him, however he can: even if he sternly dismisses anything to do with Kenway’s more wide-reaching ambitions.

Contrary to popular perception but in-line with historical fact, Blackbeard is not a bloodthirsty killer but rather, a keen strategist, who understands the value of image over action, at least as it relates to his personal brand. But even more than Hornigold, he is wholly committed to Nassau and is disgusted to see so many turn away from once bright-eyed idealism, doing whatever he can to secure the Republic’s future.

Bonnar, hitting Blackbeard’s notes of disillusionment well then, as Nassau collapses and he begins to doubt the pirate’s way, albeit, just before karmically-delivered repercussions see his life cut short (in the closer strokes to recorded history in this respect, impressively close).

Other historical portrayals, like pirates Stede Bonnet (James Bachman), Calico Jack Rackham (O-T Fagbenle) and Templars Laureano Torres (Conrad Pla) and Woodes Rogers (Shaun Dingwall) are all very well done, if not granted the same amount of narrative opportunity, comparatively: though Rackham, to be fair, plays a minor but key role come the second half of Black Flag while Bonnet, after being a major presence in the game’s prologue, is quietly written out, with only passing reference to his real-life fate (hung by the neck until dead in 1718).

Though on the reverse, as Bartholomew Roberts, Oliver Milburn’s performance is a slow burn.

And at first, there really isn’t much to make of him.

A man of few words, hounded by both the Assassins, Templars and Edward thrice for a mysterious connection, to a mysterious place, nobody can quite explain. But as is true to historical record, when he finally takes to piracy proper, in 1719, it is with a zeal that none of his peers can match. A silver-tongued sociopath who, aware of his true nature (as a reborn Isu), cares little for the path of gleeful mayhem he sets upon more than one ocean.

Playing on Edward’s hubris to his own ends, only to betray his fellow Welshman with a “shoulda-seen-it-coming” callousness Milburn just relishes in executing (unexpectedly, with far more to chew on when compared to his similarly-motivated modern-day character).

The closet thing to an overarching villain in a game where the Templars aren’t drawn as explicitly evil for most of the narrative, Roberts is great fun to watch - as is Sarah Greene as Anne Bonny, though the bulk of her screen time is mostly saved for the final third. Making a strong impact regardless, in taking on the role of the Jackdaw’s quartermaster following Adéwalé’s departure from the post.

A charming young woman who takes no disrespect and dreams of adventure, despite this, Greene presents a believable sadness she carries following her incarceration in Port Royal. Finding a respect of sorts in the Assassins even if, by her own admission it is not a conviction she will maintain. Her final fate then, as in real-life, left unknown but coloured with a what-might-have-been possibility that lands quite well.

Bound more tightly by historical fact, as Mary Read, Olivia Morgan captures a similar spirit, though in a much different way.

As when Mary is first introduced, it is as “James Kidd” the supposedly illegitimate son of the famed William Kidd. A quiet but deeply observant pirate who takes great interest in Edward’s potential and his tales of such-named “Templars” in Havana, in addition to the prize they’re after.

In time, however, Mary reveals not just who she really is but her purpose, as well: she is an Assassin and while admonishing Edward for his general flippancy and drive for profit, continually believes he is a better man than he presents, hoping he will find, within the Creed, a natural calling, just as she has.

It is a strong characterization - for one, because yes, what is indisputable about the historical Mary Read is that she was known to dress as a man in order to move more freely throughout the West Indies and this is played to effect. Mary, as James, is one of the first on the ground in Nassau and though she acknowledges some similarities between what the pirates are trying to build and the Assassins, it is to the Brotherhood where her loyalties truly lie, though caught between two worlds, she often is.

And so, arrested alongside Anne and Rackham, she later succumbs to ill health in prison following childbirth. Though not before pushing Edward, with her final words, to consider something beyond himself.

Morgan’s delivery is strong throughout (as she oscillates between Mary and the James Kidd persona, notably) but more visibly in those heavier emotional moments.

As one of the few people who can truly get through to Edward, her words carry weight and Morgan makes sure that each one lands.

On the periphery are Black Flag’s fictional characters but each is given such personality, their smaller roles within the narrative feel like missed opportunities, in the best way.

As in, it would have been cool to see them more.

As Caroline, Edward’s estranged wife, Luisa Guerreiro is present only in a few flashback sequences yet her sadness, her frustration at her husband’s chosen path, is evident.

There is too, Havana bureau leader Rhona (Lynsey-Anne Moffat), who has a charming, somewhat flirtatious back-and-forth banter with Edward or Kingston-based Assassin Antó (Kwasi Songui), who comes to foster a quiet, mutual respect with the pirate, once he allies himself with the Brotherhood.

Ah Tabai (Milton Lopes), the Caribbean Mentor, fares similarly.

Initially distrustful of Edward, especially after his actions in Havana, he sees, as Mary does, his ability and despite his wariness, trusts her judgment. When Edward admits his wish to change course, after embracing the Creed, Ah Tabai accepts him with open arms and tutors him with wisdom and a steady hand. Lopes, bringing a healthy amount of gravitas to a man who has dedicated his life to the cause.

In totality? Black Flag’s supporting cast, bolstered by its writing and performers, remains perhaps the strongest and most memorable in the series. An incredibly well-earned distinction, considering some impressive competition.

Though it is its leads who, mostly actively, live up to this standing.

Performances (Leads)

Rather famously, both Matt Ryan as Edward and Tristan D. Lalla, as Adéwalé, brought a robust sense of personal character to their roles. Edward, a Welshman from Swansea, just as Ryan is. Adéwalé, shown to be Trinidadian, in speaking to Lalla’s heritage (by his own acknowledgement).

But beyond those more minute particulars, each brings such lived-in presentation to their characterizations, one is drawn in, right from the jump.

Be it in the physical nature of their on-stage performance capture or their work in the booth, Ryan and Lalla, build a strong, effective repertoire between their characters, in addition to an individualism.

Two men who have lived drastically different lives yet find themselves quickly becoming close friends and collaborators both, as captain and quartermaster aboard the Jackdaw.

Yet, they come to find, as the years past, a growing strain within their views of the world. Piracy, freedom and the cost of wealth above all else, as Edward becomes consumed with finding The Observatory and Adéwalé angles for a more fitting calling.

Though Lalla’s sheer presence alone is clear.

A former slave who found his way to piracy, Adéwalé is a mostly stern and serious man, though with a sly, subtle undercurrent of charm. That, which he isn’t afraid to use, in working to counterbalance many of Edward’s moments of off-the-cuff enthusiasm.

He believes in what Nassau represents yes but has been hardened by the world in the way Edward and many of their allies haven’t been. Principled in a way that often seems unconventional, given the more rowdy company he keeps.

Lalla however, through his delivery, brings these elements together in a way that makes Adéwalé tremendously endearing, searching for meaning in something that isn’t just the next prize or the possibility thereof.

To this end, he cautions Edward repeatedly regarding such heavy-headedness, more than once, in his dealings with Charles Vane and Bartholomew Roberts both, seeing in them, little but destructive self-interest: that which he knows Edward doesn’t possess in the same malicious way but nevertheless seems insistent on bringing down upon his crew.

Adéwalé then, coming to realize that it is with the Assassins, knowing of their mission, for which he aligns far more.

The fight for freedom, for all peoples, not just a select few.

In time, he inspires Edward to do the same and while his former captain eventually travels to England to join the Brotherhood there, Adéwalé remains in the Caribbean, to challenge the Templars from wherever they might strike next. The growth shown then, in Freedom Cry, is immediately apparent - Lalla, stepping into the protagonist role with great skill, with Adéwalé finding strength in both his own conviction and the Creed, as it guides his hand against the sickening injustice of Port-au-Prince’s slave trade.

Calm, kind and wise to his allies but unflinching in doing what is right. Something that would be built upon even further in Black Flag’s sequel, Rogue, which sees Adéwalé, years later, now a mentor of sorts to the Colonial Assassins in their never-ending fight against the Templars (even if his story there ends rather abruptly).

In 2023, Lalla spoke on the importance of continued representation, not just in video games but in all art, across all mediums, while recognizing the role his portrayal of Adéwalé has had in that advancement, across a binding, three title arc.

A deeply human, genuine character brought to life by a simply fantastic performance.

And Edward?

Praise must be given to Matt Ryan in spades here, for the hold he has on the character, multifaceted as he is, is incredible.

Brash but affable, devilishly charming but equally frustrating, as he slides further-in-further, throughout Black Flag’s story, into growing obsession.

Yet, there is an honesty present, in its entirety, that informs every minute detail of Ryan’s performance from the very beginning.

From the moment he is met, Edward makes no qualms or compromises regarding his ambitions. Having come of age in quiet station, without advancement, without a future he could fully call his own, he sets out for the West Indies. To find possibility as a privateer and later, unabashedly, as a pirate.

For others to look upon him and say he matters, even if that praise comes from ill-gotten gains, well, that is a price he is more than willing to pay.

It is what drives him to The Observatory in the first place.

Not totally understanding it but believing, no matter how many obstacles he must clear, that it is a prize worth pursuing. He doesn’t then, to this end, have the same level of commitment to the Republic in Nassau that his mentors do. Invested yes, in what it represents in the moment, a life of leisure and small luxury but not quite seeing the bigger picture possibility. To his individual aims, it just doesn’t match up - its collapse, if nothing else, a stepping stone.

Similarly, he initially expresses a fair measure of bewilderment upon his introduction to the Templars and Assassins both, more than willing to bend their philosophies and tools to his benefit. This, a general first for the series to this point, a protagonist who has no interest in a centuries-long conflict that has encircled the globe, merely how he can profit from it.

And yet, Ryan’s performance, in tandem with Edward’s growth and that of the writing, is paramount and expertly delivered.

For as much as he presents a generally honest front of carefree ego, Edward’s relative ambiguity is rounded out by a pronounced humanity.

He holds close a particular moral code and cares greatly for his friends, holding their opinions in the highest regard. Even if, for Mary and Adéwalé specifically, it comes with increasing amounts of irritation.

He doesn’t see himself as a man of belief and doesn’t care too.

But as he loses Blackbeard, loses Mary, Hornigold, to the Templars and sees the heartlessness of Vane and Roberts in full view, he slowly begins to understand why there must be barriers to unchecked power, to the type of corruption the Templars practice, to the type of crusade he himself has spent years embarked on. His experience at The Observatory and later, his time languishing in prison, crystallizing these feelings: what is a man though not by the measure of his wealth but what he fights for?

Understanding, in the wake of much personal loss, that the Assassins can offer him not just redemption but something even greater - purpose.

This, what he has been truly seeking.

And as he commits himself to their cause in Black Flag’s final act, it is perhaps where Ryan shines the brightest.

Edward, humbled but having discovered an inner resolve he didn’t know he had, in seeing the potential for wisdom in the Creed, as he strikes down the Templars and pirates he once allied with. Not for his own advancement but instead, for those that would fall under their grasp, should they find The Observatory first.

A maturity, weathered but hard-won, for which Ryan embodies brilliantly, in what remains one of the best lead performances in the long-running series wholesale: so complete, vulnerable, in its overall character arc and presentation.

Although it was, ultimately, just the start of Edward’s story.

Be it the game’s companion novel, the same named Black Flag or the Forgotten Temple, the canonical sequel comic which follows his exploits, now as a member of the English Brotherhood in the years following his time in the Caribbean, battling to secure a Piece of Eden over the Templars. Trying to reconcile his past with marriage, fatherhood and the mission. There is too, III’s companion novel, Forsaken, which sees him, as an astute, wiser man, leading the Assassins in England. Beginning to tutor his son, Haytham, to follow in his footsteps, just as he is betrayed by treachery from within his own inner circle.

Though maybe it is the small but important role the character plays in Syndicate, well over a century following his death: as the Assassins aiming to retake London from Templar control look to uncover the secrets he left behind.

All of it, in some way, tying back to Ryan’s fully-realized interpretation of the character. The legs, to his credit, his portrayal continues to have.

Outro

Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag doesn’t hit on all of its swings.

Its on-the-ground combat is wildly unpolished, as is the parkour. The stealth isn’t anything special and from mission constraints to design, it can invoke frustration.

The pacing of its historical story can hit a few snags and does so, visibly, near the end, as it races somewhat to tie off quite a few loose ends. The modern day portion is somewhat intriguing for the committed series fan but doesn’t offer much besides.

But for where Black Flag excels, it excels.

The open world and unique flavour of its exploration loop, even a decade-plus later, remain a standout in gaming’s ever-evolving, third-person space, as does the pirate-fantasy driven, ship-based combat.

The narrative, both an excellent pirate tale and a larger examination of the franchise mythos is both strongly written and incredibly engaging, while having a great respect for the known historical period it is fictionalizing. From the richness of its period-true dialogue to an emotional maturity that extends, as well, to Freedom Cry.

The performances, both supporting and leads are, when taken collectively, probably the most noteworthy to come out of the series thus far - everyone, it seems, was up to the task.

Unconfirmed rumours regarding a possible remake have circulated around Black Flag for a while now and perhaps (following this writing), in the wake of Shadows’ release, more will be officially revealed there. But such a development, it shouldn’t take away from what it first delivered on, back in 2013.

A title of artistic strength, on so many fronts.