Red Dead Redemption: An Off-Balance Retrospective.

People don't forget. Nothing gets forgiven.

Table of Contents

Regardless of the medium, be it literature, film or in this case, video games, there are always benchmarks, goalposts, to reach for.

New ideas. new mechanics, new hardware.

As a byproduct then, of this evolution, it is understood that placing too much stock in just one title specifically, it can be shortsighted.

Disingenuous even.

But the broader influence of 2001’s Grand Theft Auto III really cannot be overstated.

No, it wasn’t the first title, strictly speaking, to play host to its various gameplay elements but the connective tissue was found in how developer Rockstar Games brought each one together, virtually inventing the third-person, open world template as it continues to exist today.

And though others, to varying degrees, would put their own stamp on the formula, Rockstar, primarily through their crime-chaos simulators, would remain well-and-away the gold standard. 2008’s Grand Theft Auto IV then, it saw this loop nearly perfected, not just mechanically but regarding their storytelling acumen, as well: their usual satirical malice, crossed with dark commentary on the truly fictitious nature of the American Dream.

But even so, familiar as it may have been in many respects, Rockstar’s next title, Red Dead Redemption, would move even further beyond those confines.

Towards something different, heavier, more strictly human.

A spiritual successor to 2004’s Red Dead Revolver and in time, becoming the closing stanza to 2018’s prequel title, Red Dead Redemption II, Redemption turns fifteen this month, having first released in May of 2010.

Not without its missteps but still, a title of noticeable strength and artistic conviction, even now, a decade and a half later.

And today at Off-Balance, we’re taking a look back.

Saddle up.

Intro (Red Dead Redemption)

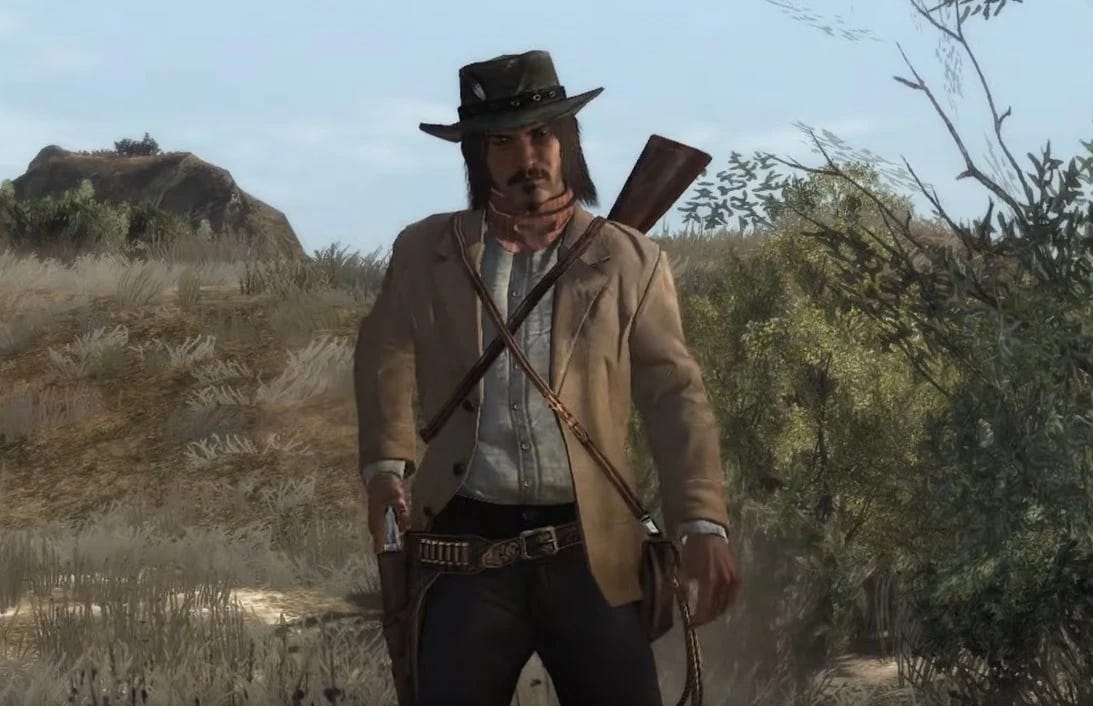

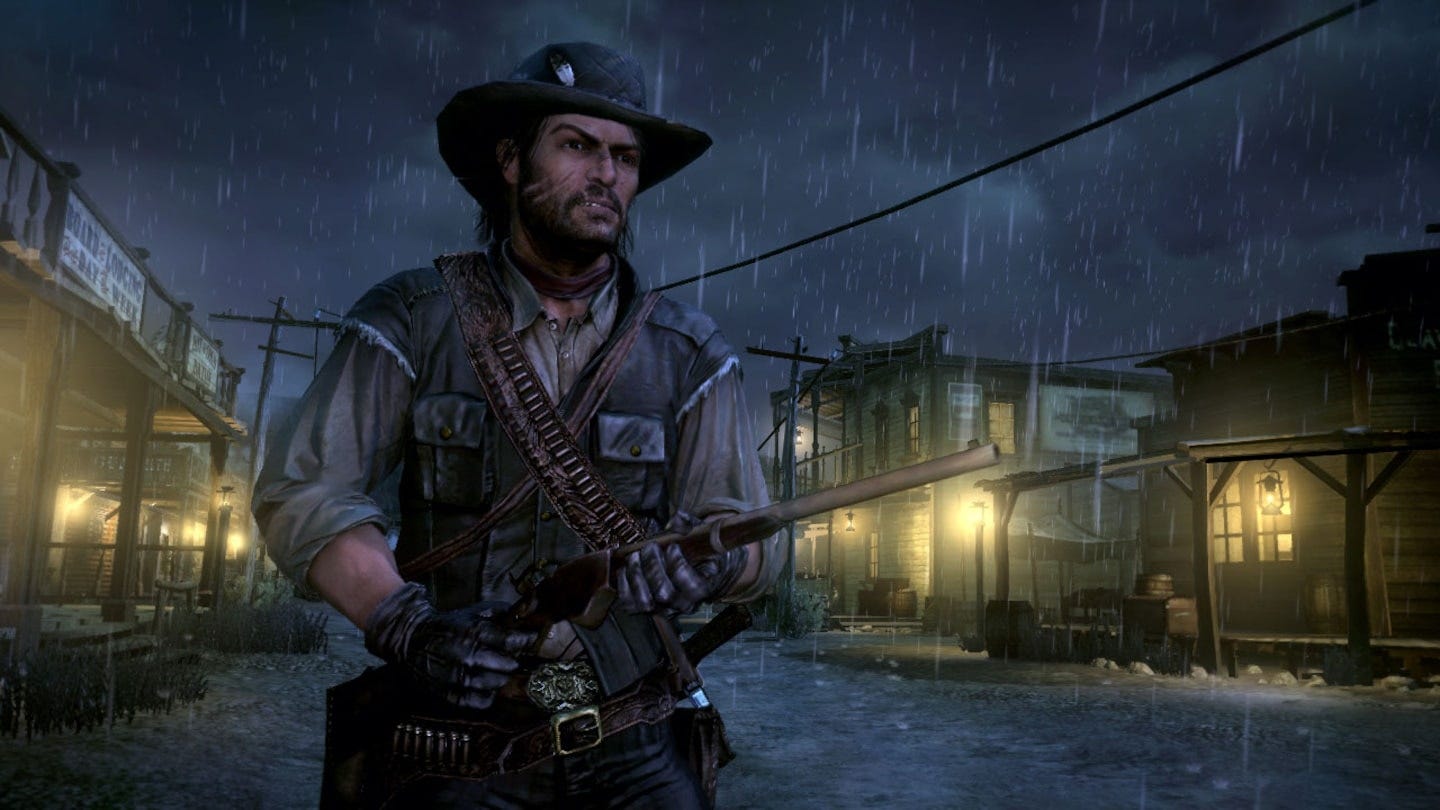

Come 1911, whatever is left of the Old West has almost well-and-truly faded into myth… yet from the ashes, emerges former outlaw John Marston (Rob Wiethoff).

Years ago, John rode in the notorious Van der Linde Gang, said to be terrors of the West, robbing and killing as they went.

Though now, having long put gunslinging behind him, he wishes only to live out the rest of his days in peace.

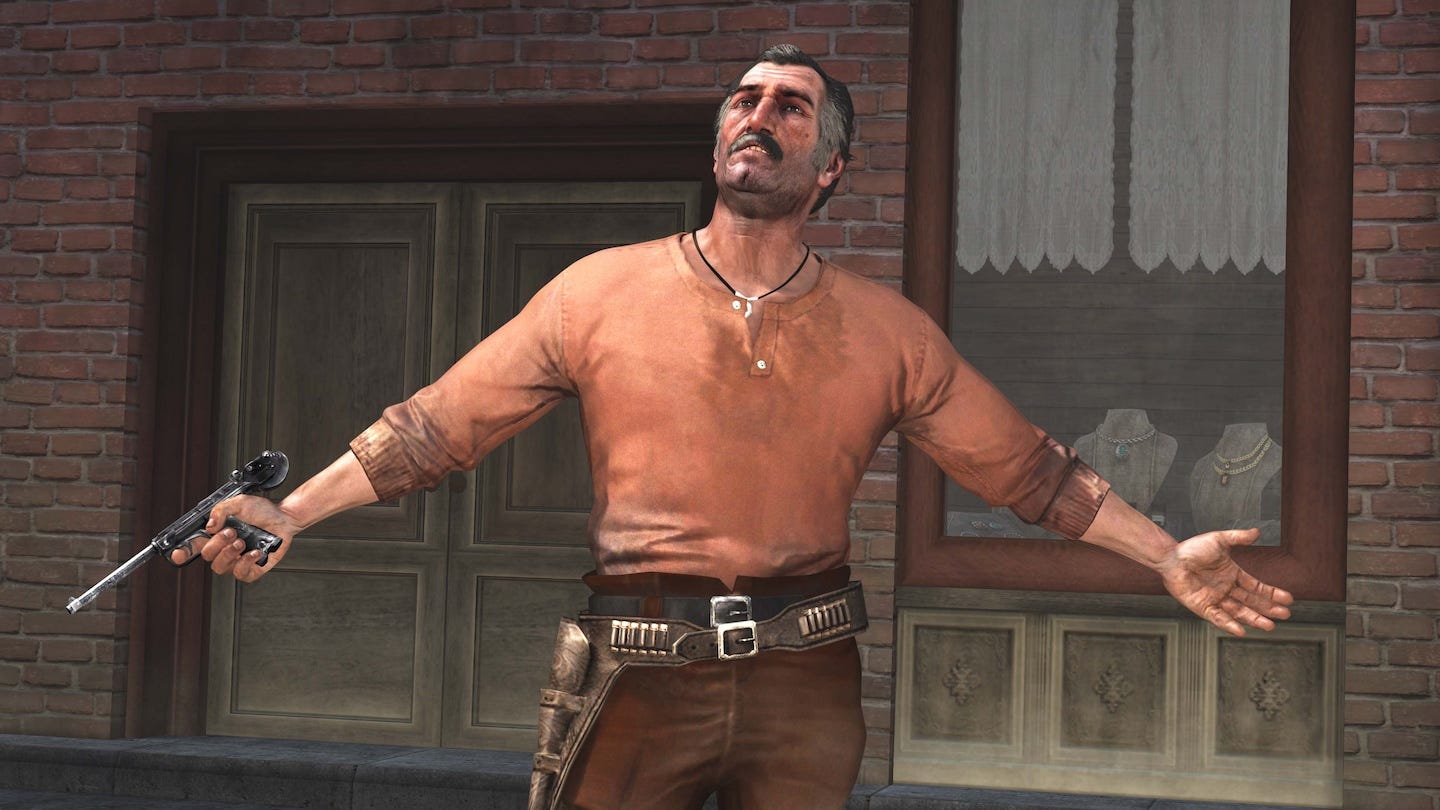

But when his family is kidnapped by government agent Edgar Ross (Jim Bentley), in order to secure their safety, John is strong-armed into tracking down and eliminating his former compatriots: Bill Williamson (Steve J. Palmer), Javier Escuella (Antonio Jaramillo) and one-time mentor and gang leader, Dutch van der Linde (Benjamin Byron Davis) himself.

So as he moves through a (fictionalized) Southwestern United States and later still, into Mexico, gathering allies and fighting rebellion as he does, all in pursuit of those he once called his brothers, John must face, head-on, a past long thought dead and buried.

Realizing that, no matter how hard he tries, some demons are inescapable.

So while the strengths of Redemption’s base framework are immediately apparent, there must still be a larger focus. This then, present in one of the game’s most visible pillars: the combat.

Combat

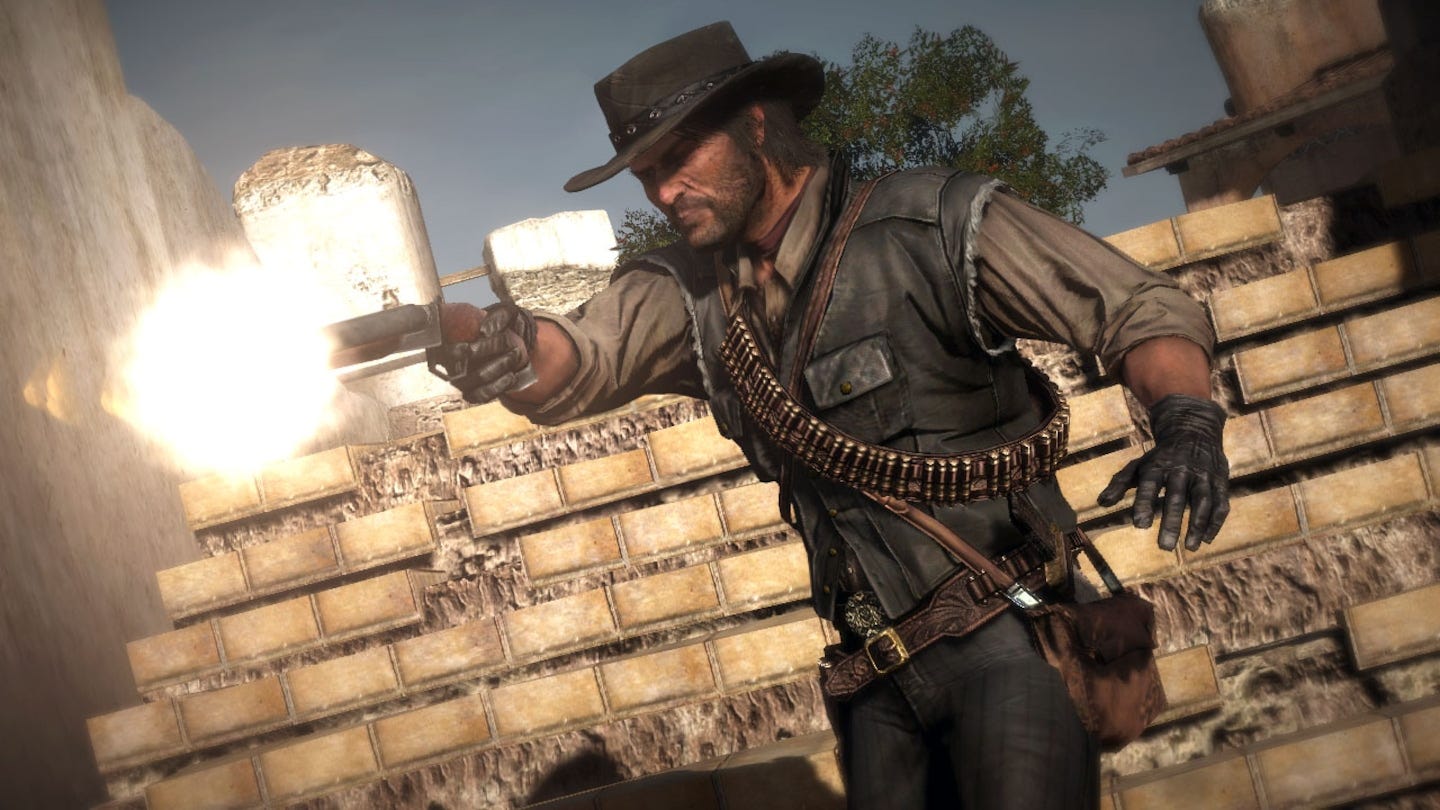

Broadly, given its status as a direct corporate successor, Redemption follows GTA IV’s third-person cover-shooter combat blueprint, albeit, with its own additions and the trappings of its period setting understood.

John, as a longtime outlaw-in-remission, can wield an assortment of firearms with skill, divided into different classes, from classic six-shooters and high-ammo repeaters to far more blunt, front-facing shotguns.

Each individual weapon has its own unique stats (damage, range, capacity, etc) meaning, in theory, there is a certain push to experiment, be that by unlocking weapons through story progression or spending hard-earned cash at gunsmiths, particularly come the final third of the campaign (where semi-automatic guns, highlighting the might of the new century in all its glory become available and put the cowboy of yesteryear to shame).

In practice, however, once the player finds a measure of comfortability with the mechanics, there isn’t much stopping them from sticking to their guns of choice for the vast majority of any one playthrough, even if, from time-to-time, an odd damage buff may work in their favour.

The weapon wheel returns, accessible via a hold of the left-trigger, allowing for the swapping between guns, with little in the way of practical interference. That being, if the player wants to instantly switch from a rifle, sniper rifle or shotgun they can do so, as those weapons, though placed on different spots on the wheel, all occupy the same, in-game, long-arm holster (likewise, for sidearms).

Yes, returning to Redemption means not having time slow down when accessing the wheel (as is the case in both of Rockstar’s succeeding titles, Grand Theft Auto V and Redemption II) but it also adds a element of genuine pressure to every encounter, particularly on hardcore difficulty - forcing players to consider their options in this space quickly and decisively when under fire.

Speaking to this, the cover system, responsive and functional, sees that John isn’t hit with stray fire unless the player is in active motion or poorly positioned and while there isn’t, by design, much to be said for sheer enemy variety or their instincts for self-preservation, the impact physics are well defined and each shot lands with a fair amount of weight behind it, depending on the weapon chosen.

Repeaters and rifles are best against large groups but if the player wants to make a statement, shotguns, naturally, are one hell of a messenger.

And while “Dead Eye”, the bullet-time mechanic featured in Revolver returns, it has much more prominence this time around.

A right joystick press will activate Dead Eye, reload any equipped weapon and slow time to a crawl, allowing players, following a series of sequential upgrades, the ability to line-up their sights, manually mark targets and fire off a series of shots in rapid succession.

Though it can seem like something of a cop-out, giving the player such an express advantage, a key component in the combat flow, Dead Eye quickly becomes one of the most relied upon tools in the player’s arsenal: from panic shots when overwhelmed or granting the confidence to walk into a gang hideout even when greatly outnumbered.

In support, the duelling system is presented with a great deal of classic Western flair - showdowns in the street, eyes, narrowing, etc - while not being too easy either, within a tight timing window, while extraneous items such as fire bottles and dynamite can be used to create breathing room when needed but will rarely, if ever, see broader use beyond specific story moments.

Similarly, there are some very light stealth mechanics (at around the halfway mark of the story, most notably, the player will gain access to throwing knives) but any sort of stealth is incredibly situational and really doesn’t have anything worth noting beyond its baseline implementation.

When one needs to use it, it works but it is not anywhere near a core piece of the experience.

It does track though, to be fair.

John, being a gunslinger, is not an all-encompassing warrior and Redemption’s combat speaks to this. It is prompt, deliberate and though definitely far faster and looser when inevitably, unfairly, compared to its prequel, continues with GTA IV’s heavier dose of realism. The player, though immediately a cut above their rivals isn’t invincible either and if too reckless, will be dropped in just a few hits.

Danger, after all, is ever-present in the far reaches of the West and one must always be prepared, as they venture outwards, with their finger on the trigger.

Open World + Exploration

As John sets out on his quest, it is to see that he alone is not the only one who pines for the long-ago days of the West. Understanding that, in comparison to its metropolitan forebears, there is only so much Redemption’s open world, given the nature of its setting, can do to truly innovate on that established template, it choses then, to strike out in its own way: the thematic overhang of modernization, ever-present.

The last days of the wide-open frontier, laid bare. Melancholy in one hand, with a Spaghetti Western twist in the other.

Broadly an open world title, one isn’t given free reign to totally explore right from the jump, the structure of Redemption’s story meaning the player is locked to specific regions until certain story benchmarks are completed.

Settling into an enjoyable rhythm then, as it relates to the open-world loop.

Perhaps it is ponying up in one of the numerous table games - poker, blackjack, Liar’s Dice -, breaking horses for a small profit or in larger communities, taking on a post as a nightwatchman.

In risker pursuits, if the player is feeling brave enough they can go bounty hunting, in repeatable missions, which come with something of a learning curve. Fighting off waves of enemies, though with a touch of finesse, in order to bring a target in alive.

Ambient combat and exploration challenges, treasure hunting, clearing repeatable gang hideouts or working through the checklists of the game’s various set outfits (completion here, providing a handful of differing gameplay markers, from combat buffs to, in one instance, gaining the ability to cheat at poker).

In terms of raw depth, Redemption’s activities land more openly on the other side of the meter but there is always something to keep the player engaged, always something, to pursue.

Stronger, faster horses meanwhile, if the player finds they could use a boost of acceleration in more explosive story moments, can be gained by buying their deeds at general stores or going rustling, although these gains are at best, very much incremental, even

The hunting and botany mechanics, similarly, are super straightforward - pick, point and shoot - but selling specific gains in different areas of the world can prove quite profitable, this, appreciated in a game where money, hard-earned, isn’t provided hand-over-fist. To this point, Redemption can only be manually saved at set-points, either at John’s campsite in the wilderness or at purchased safe houses dotted across the map.

Frustrating at times yes, such a mechanic, outside of the Souls-like genre, mostly a relic of the late 2000s gaming era but it also encourages a distinct approach in navigation and exploration both. And sure, while fast travel is an option from the campsite, even to specific waypoints (and during missions) there is undeniable charm present in the Dollars-trilogy-esque vibe given off by Redemption’s world.

There is a fair amount of moment-to-moment dynamism present (yes, stick-ups, coach robberies duelling lawman and outlaws, etc) but most of the time, to form, John is alone, isolated.

Raging against confines he can’t change, as he fights to secure his family’s future.

Fifteen years on, it can be easy to point towards the relative quietness of the world as the result of hardware limitations, undeniably true to an extent but it is something, conversely, that Rockstar and their team leaned into.

Not just narratively but within the larger world-building overall. The art, sound and structural design, the sheer ambience, all pointing towards a consistently memorable, player-first experience.

Streaking through the desert as the sun, bursting with pink hues, sets in the distance or passing through Armadillo, the last true frontier town. The vastness of Mexico’s canyons and the remoteness they inspire, up against the brutality of a revolution that sees them stained with blood, wandering through the village of Chuparosa at night or the northern area of Tall Trees, masked with snow and secrecy.

Each area, being uniquely realized in service to this thematic vision, only in eventual contrast, to the modernized port city of Blackwater: cobblestone streets and automobiles, hotels, not watering holes.

The law, not frontier justice and everything, for the forgotten age of gunslingers, that encroachment represents. John, the player, feeling both at home but startlingly out-of-place too. In tandem, is Redemption’s score, co-composed by Bill Elm and Woody Jackson, which works diligently to both capture this dichotomy and lament the reality of it, as well.

In promotional interviews, the duo discussed the specifics of their musicianship, both individually and in collaboration. From chosen instrumentation moment-to-moment as it related to the gameplay flow - jumping from exploration to combat or how the ambient sounds of New Austin and West Elizabeth, sonically, build from the same base yet land far differently, for example, than what is heard south of the border, in the Undead Nightmare DLC (or even within the game’s four vocal tracks).

For as John moves through the world, the player must be mindful of two progress bars: one, reflecting his honour, certain actions, plainly enough, good or bad, showcasing how far back he has or has not slid into his former outlaw ways (with gameplay benefits and a “Wanted” system to boot but no narrative bearing) and the other, his fame.

The reluctant return of John Marston to the open road, it sees his name, slowly and surely, be spoken of.

From whispers to being visibly recognized as a man of fortune, almost humorously, to his growing indifference.

For John’s tale of firmly closing the book on his past to reunite his family, it is, though well-supported by the combat and open-world loop, the core driver of Redemption: incredibly dark, cynical and highly cinematic, with an odd measure of poignancy dashed throughout - caught though it can be at times, between pacing and presentation.

Story (Base Game + DLC)

Even acknowledging the inherent grandiosity present within the basic set-up (an outlaw’s odyssey across the dying West) Redemption’s story, primarily, is pretty neatly structured into three distinct, if similarly-presented acts.

John, arriving in a new area, be it New Austin, Mexico or West Elizabeth, although he’d much rather go at it alone, realizes that in order to succeed in his mission, allies are in order, although their help and trust are, rarely, easily won.

A series of favours, exchanged for another, in further return.

It is very much in the Rockstar mold, it is true, most missions, with some variation, following the same script - travel here, listen to an extended stretch of back-and-forth dialogue on the way, get into cover for a shootout or showdown as needed upon arrival - but there is, despite this, enough narrative and character weight present to carry things forward.

For try as he might, for most of the story, John always seems to be two steps behind.

And after his first attempt at taking Bill in, with diplomacy, sees him shot and left for dead, John steadily begins building up a fighting force, to take on his former outlaw-in-arms and his gang, head on.

Though as he does so, Bill narrowly escapes into Mexico, forcing John to follow in hot pursuit, only then to find himself pulled, as he is, directly onto the various fronts of the ongoing Mexican Revolution: from rebellion and tyrannical government to isolated vigilante justice

But even as the metaphorical noose tightens, his focus only becomes stronger, more determined.

Eventually cornering Bill and Javier both, John returns to America expecting his contract to be honoured, just to be leveraged by Ross once more. His family will be released to him, on the condition that he takes down Dutch, who has totally devolved, per John’s telling, into the polar opposite of his previous standing: an indiscriminate and deranged killer.

Dutch however, refusing to see his story end on anyone’s terms but his own, commits suicide, though as he does, tries to impart one last piece of wisdom into his former protégé - they won’t rest at him alone.

And prophetic this comes to be, as not long afterwards, Ross leads the US Army to attack the Marston homestead, to finally end what remains of the Van der Linde Gang once and for all. Realizing then, that he can no longer run from his past, John, after seeing his wife Abigail (Sophia Marzocchi) and son Jack (Josh Blaylock) to safety, dammed as he is, makes one final stand and is gunned down against impossible odds.

Yet three years later, as war begins in Europe, Jack, now alone, confronts Ross, demanding justice. Ross dismisses him but Jack, relentless, promptly shoots him dead.

Avenging his father but in doing so, becoming an outlaw… the very life his parents fought so hard to shield him from.

All-in-all, the highest points of Redemption’s main narrative, still, bring forth what makes Rockstar one of the best in the business when it comes to their storytelling chops: a rumination on love, war and sacrifice and the cost, inevitably, that must be paid for all three.

It is too, dark as hell, not looking to sugarcoat its heavier themes or narrative nodes, even if many of those coverings are more surface-level: sexual violence and abject hedonism or the evils of the industrialization complex.

Though where it stumbles, most visibly? It is within the practical application of its pacing.

Each mission, appropriately, is presented to the player with the upmost urgency, John’s goal, so singular, so all-consuming, it simply doesn’t make sense to slowly meander through the world for too long, as one might in the usual third-person space.

It can even be felt in the side-missions, the “Stranger” threads, for which John stopping to help someone gather flowers, blackmail politicians or get caught up in the drug trade, for example, with a few exceptions, just don’t gel that strongly with his personal focus.

He just has bigger fish to fry.

This commitment however, as a byproduct, it can create a feeling of repetition, particularly in the game’s second act.

The Mexico arc, spinning its wheels for what becomes hours on end, only for its resolution, ultimately, to not land with much impact, relative to its build-up - while the deception of the Mexican people overall and John’s positioning in their story teetered on the line even back in 2010 and admittedly, hasn’t aged too flawlessly in the intervening years.

Of more strength, in hindsight, is how well Redemption works as an unintended second act to its prequel: more often than not, John speaks of his time as an outlaw curtly, vaguely, in character yes but also not establishing any sweeping plot points beyond the basics (he was shot during a robbery and left to die, etc). Though his few face-to-face moments with Dutch do imply an extended length of time, a decade or more, between any previous interaction… despite it being, canonically, only four years… but considering the eight real-world years between titles, knowing what was and wasn’t conceived during Redemption’s development, it all fits together, to Rockstar’s great credit, almost seamlessly.

Then, in contrast, it is seeing that self-seriousness be purposefully stripped away in the game’s major DLC episode, Undead Nightmare.

Narratively unconnected from the rest of the series, it sees John set out across the West once more, only this time, to stop a zombie apocalypse: from base defense to tweaks to the combat loop, Nightmare takes the already solid foundation and adds a pulpy, grindhouse film, a throwback in the high-octane genre fiction style, to success.

Further bringing Redemption to life however, are is its characters, its performers, starting with the supporting cast.

Performances (Supporting)

While the nature of the story means there are no characters that truly carry over act-to-act, Redemption does have a handful of standouts amongst its supporting cast.

One of them, is Kimberly Irion as rancher Bonnie MacFarlane.

She finds John in the story’s opening moments, having been shot and left to die and saves his life, simple curiosity, by her own admission, getting the best of her.

And while she is one of the only people John, allowing his hardened façade to fall away, truly opens up towards regarding the reality of his situation, she also holds him to a measure of account: she is deeply grateful for his help around the ranch and later, for saving her life in return but is doubtful of how he speaks of the Van der Linde Gang’s heyday, disregarding the Robin Hood romanticism that colours portions of his recounting.

Irion then, strikes a really strong note of character: Bonnie, a woman who answers to no man and can handle herself with ease and yet, strives for more beyond the familiar that has come to define her life.

Earning John’s kinship in a different way is Ross Hagen as Landon Ricketts, a once former gunslinger now operating as a self-styled vigilante in small-town Mexico.

He comes to see something of a younger version of himself in John and while a quasi-mentor of sorts, in sympathizing with his predicament (having lived “the life” himself) isn’t above openly challenging him either: pushing John to consider the human element of the Revolution, of which Marston, in his single-mindedness, just can’t be bothered too.

There is great power in Hagen’s performance, despite the fact that he only appears in four missions total and in what became his final role, prior to his death in 2011.

Ricketts, carrying on his shoulders, the melancholy of a man whose apparent freedom was hard-won and not without regret, yet while still being incredibly dangerous, peerless perhaps, when it comes to his trigger finger as he fights the local government and their corruption - searching, though he will not say it outright, for just a modicum of that titular redemption.

Others, such as Anthony De Longis as US Marshall Johnson, Francesca Galeas as rebel Laura and Josh Segarra as hedonistic rebellion leader Abraham Reyes all add their own elements to the proceedings, playing off the narrative in their own way.

On the antagonist side, as Ross, Jim Bentley doesn’t hold anything back, a man who believes deeply in his principles but has no moral grounding behind them. This, representing the new America, rounding the corner: John towers over him but the type of power Ross holds, it is able to take a punch, if only because one can never see it coming until it is far too late.

As Bill, though the driving force of the first and second acts, Steve J. Palmer doesn’t get as much screen time as one might think but he makes each moment land effectively, believable as a one-time gunman who perhaps never got his fair due, years ago.

But now, as an outlaw of renown all his own, he will see his name be spoken of, for better or worse, as he leads a gang of dangerous, sadistic rapists.

And similarly, though Benjamin Byron Davis’ Dutch is spoken of often throughout the campaign, it is only during the final third of the story in which he physically appears - but Davis makes his mark regardless.

What makes Davis’ performance so curious, so intriguing on its own merits (without immediately colouring in the gaps to what was shown in Redemption II) is that the dichotomy in Dutch feels so striking. An undeniable charisma, shining through, a quiet respect John still holds, despite the fact that Dutch is now, far removed from his peak, little more than an utter maniac, an outlaw, with nothing to stand behind chaos.

Once, perhaps, he was a man of principle and honest conviction and Davis brings that element forward but conversely, it is clear that Dutch himself no longer believes it.

Screaming against the comforts of the modern world but forever indebted to it, as he turns the disenfranchised and aimless against the system. Not to loosen a wheel even, just to kill in its name… even if he acknowledges, in his final moments, just how far he has fallen.

Ultimately, in limited work, Davis delivers and to effect.

Though for as memorable as the best of Redemption’s supporting cast may be, most of the focus is geared towards the work of its leads.

Performances (Leads)

Pulling back, it is interesting to consider, on a more thematic level, the notes of distinction Redemption draws between its two protagonists, John and his son, Jack.

Singularly yes but comparatively as well, between the dynamic delivered by their performers, Rob Wiethoff and Josh Blaylock, respectively.

Though what makes John such a fascinating protagonist, as written by the Rockstar team and portrayed by Wiethoff both is that he doesn’t quite fit the traditional hero mold nor does he want too, either.

Articulate, front-facing and with little regard for those who waste his time, John doesn’t care much to exist in a world of pretence or misguided optimism. He has seen the supposed best of men but also, at their lowest regard as well, no doubt, too often by his own hand, as a career outlaw looking now to simply protect his family.

And right from the jump, Wiethoff takes John, this gruff, no-nonsense cowboy turned reluctant bounty man and immediately makes him one of the most endearing (and retrospectively, memorable) characters seen not just in gaming but the modern pop culture space wholesale.

Willing to acknowledge the hypocrisy in his mission - to put down his guns once more, he must first be the hand that delivers the peacemaker’s justice - but to an end he considers just, righteous.

Wiethoff, hitting each note of weariness in his dialogue, every small twitch of physicality in his larger on-stage performance capture, every layer, steadily pulled back to examine just what makes John, as contradictory as he is honest, this, in a performance that is just so well-realized.

In real-time, yes, the final days of the Van der Linde Gang were only loosely conceptualized during Redemption but Wiethoff sells the weight of this dissolution with such conviction, such conflicting emotion, one almost wouldn’t believe the reality of that production.

Though it is knowing too, on some subconscious level, that it is a past he cannot truly outrun. The honesty he displays with Bonnie, Dutch and Landon Ricketts, all in different ways, foreshadowing as much.

And having already known the power of that sacrifice previously, John can only hope that he has done all he can to protect and prepare his loved ones, as he lays down his life to keep them safe: even the smallest subtleties, right up until the end, something Wiethoff finds and doesn’t lose his grip on, not once.

But as it becomes clear, that hope John held onto so deeply, just as he took his last breath, it flew quickly to the wind.

Throughout his journey, John speaks occasionally of his family to the most trusted of his many allies but it is only after his dealing with Dutch are they released safely home - though upon their reunion, John realizes his opportunities to make up for lost time are already wearing thin.

Jack, though he loves his father, is, as well, a teenager. Believing, in the tale as old as time, that being on the cusp of manhood is enough to qualify him as such. Wanting John’s mentorship but equally so, being frustrated with his father and not afraid to say it.

His absences, his inability to fully be honest as to why, his insistence that things really are different this time, despite the impression that John has already burned through that promise more than once.

And to Blaylock’s credit, not only does he sell these aspects of Jack’s character, in what is a pretty brief storytelling window but his growth, too.

He just wants to make his father proud.

But in tracking Ross down and killing him in the name of revenge, fulfillment seems be something he is still chasing, if ever-unseen, that he finds it at all.

The cycle of violence, a damming and indiscriminate thing, for which Jack and chronologically, the series, leave to be explored in the pieces left behind.

And even in comparatively smaller doses, Blaylock lands on this well.

Outro

It is true, for all its industry and cultural wide praise, though well deserving as it is, Redemption isn’t without its share of if not open flaws per se, than missteps.

Its pacing, particularly in the second act, can often feel as though it is buckling under its own weight, the combat isn’t all that challenging without active player intervention and the open world, understandably, leans more towards ambience than complete depth (and while the industry en masse continues to slowly shift away from hardline crunch, that doesn’t excuse the working conditions Rockstar’s employees saw during development).

But the larger thematic strokes of the story, the performances, from the best of the supporting cast, to the leads, the specific feeling of verisimilitude the open world shoots for - even fifteen years later, there is certain nigh-timelessness Red Dead Redemption presents.

Mature, dark and purposeful, in a way few video games that followed it are, despite the groundwork provided.

A journey just as strong as the destination.