The Talented Mr. Ripley: An Off-Balance Retrospective.

Taking a look back at the identity theft thriller.

If you have yet to see The Talented Mr. Ripley, the movie will be discussed in detail here. Please consider this your spoiler warning.

Otherwise, if you’re looking for the Off-Balance review of 2024’s “Ripley”, the Steven Zaillian helmed miniseries, you can find it here.

And, finally, while Off-Balance will always be completely free, if you’d like to support my work in a different way, you could always potentially buy me a beer instead. Either way? Just follow the prompts below.

Thanks for reading!

Until next time,

Ryan

Ever since novelist Patricia Highsmith first brought him to the page, the latent genius behind Tom Ripley has been indisputable. A liar, a schemer, a sociopathic murderer, but man, you just can’t help but root for him.

And while Highsmith wrote five novels staring Ripley over her decade-long career (the aptly-titled “Ripliad”), none of them have had the same staying power as the first, 1955’s The Talented Mr. Ripley, the basis for a king’s ransom of adaptions and pastiche-driven imitators.

Nothing more than a small-time grifter, when Tom Ripley finds himself caught up in the lifestyle provided by an American socialite abroad in post-war Italy, he doesn't just infiltrate that world in the aim of self-pursuit - he throughly destroys it, in a tangled web of romance, deception and murder.

The appeal, from a larger creative perspective, is undeniable. A story both a product of its time (all the major adaptations have been either a contemporary effort or period pieces) yet dangerously present, as well.

Though while many-a-filmmaker worth their salt have taken on the task of bringing Ripley’s origin story to life, of those that have perhaps none have done so better than the late Anthony Minghella, whose 1999 film adaption, The Talented Mr. Ripley, turns 25 this month.

Featuring a “who’s who” of actors at the top of their game, stunning on-location work and a sense of creative commitment overseen by writer-director Minghella that never wavers, Ripley is not just an adaptation of great strength but a terrific movie on its own merits: an emotionally-charged thriller that remains as impactful now as it was upon release.

Come - to Mongibello we go.

As he moves through a paltry existence in late 1950s New York City, struggling conman Tom Ripley (Matt Damon) longs for more than the hand he has been dealt - he just doesn’t know how to get there.

But following a chance encounter with shipping magnate Herbert Greenleaf (James Rebhorn), he finally sees his opening.

Greenleaf wishes to bring his wayward and headstrong son, Dickie (Jude Law) back home from an extended sojourn in Europe and falsely believing Ripley to be a former Princeton classmate of Dickie’s, recruits him for the task.

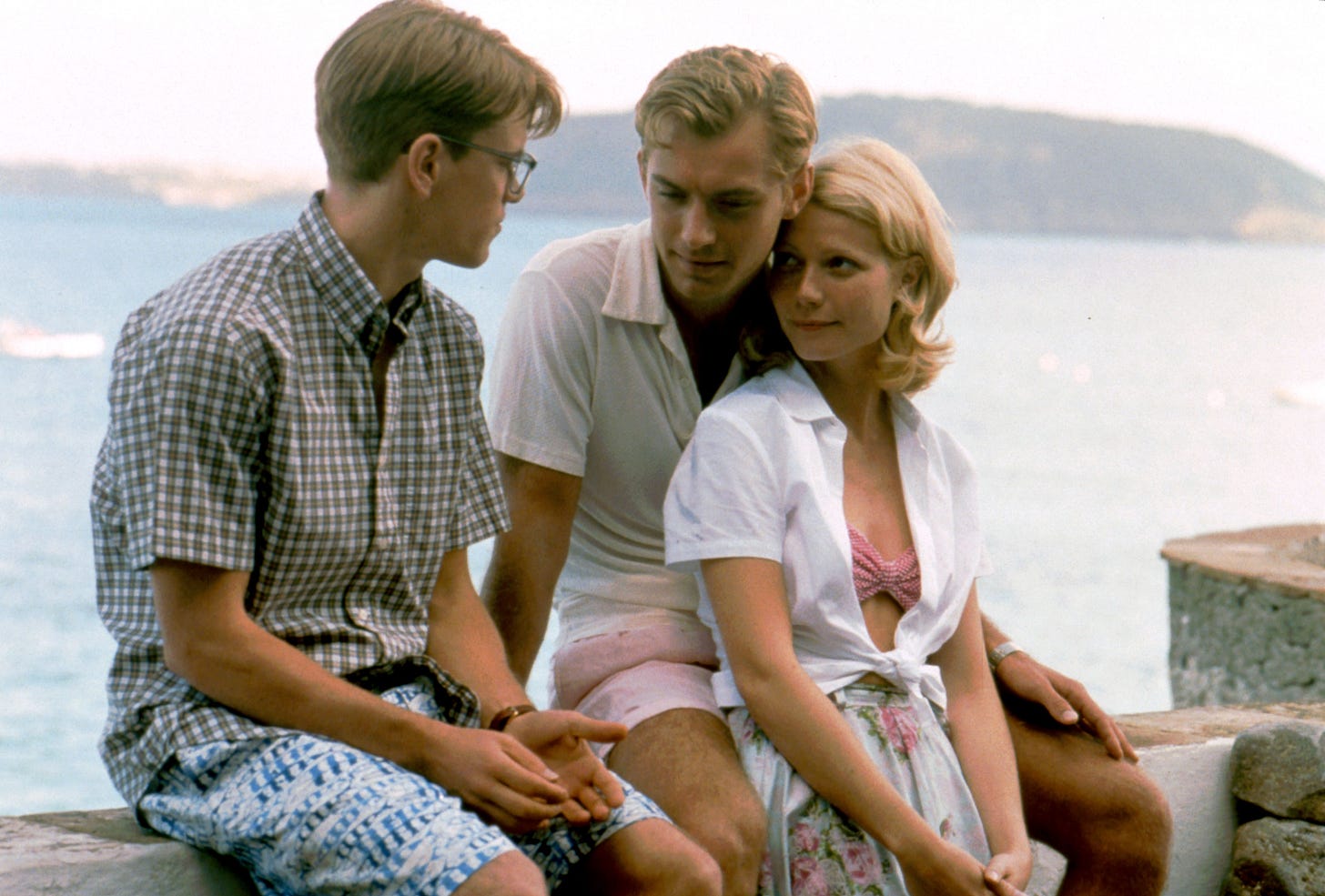

Though once he arrives in picturesque coastal Italy, it becomes apparent that Ripley has no intention of completing his mission, becoming obsessed not just with the lifestyle Dickie provides but the man himself. So when the heir and his social circle (Gwyneth Paltrow’s Marge and Philip Seymour Hoffman’s Freddie), begin to grow wary of his presence? Ripley puts his greatest con into motion - taking Dickie’s life for his own, no matter the cost.

It is a testament then, that the movie excels on various fronts, given the potential one-sided nature of the material, but particularly so, within its presentation.

Shot entirely on location (save for the opening stanza in New York), the film’s rendition of Italy is an absolute spectacle, awash in colour and visual character. Be it Minghella, the film’s location scouts or cinematographer John Seale, most prominently, all working in tandem.

From the sweeping vistas and intimate alleyways of Southern Italy, notably the village of Positano (standing in for the fictional Mongibello), the smoky haze of a jazz club or the deep reverence for the architectural marvels/local landmarks of Rome and Venice both. And yes, inescapably, in this respect the movie draws comparisons not just to the previous Ripley adaption, René Clément’s Purple Noon but also medium tentpoles sporting a similar visual language, such as Roman Holiday and La dolce vita. But it finds a unique voice all its own despite this, one rich in detail and inspired minute.

From the period-appropriate set-design, to the work of legendary costume designer Ann Roth, whose wardrobes for each character feel full and perfectly realized. Ripley’s second-hand suit jackets, Marge’s summer-casual look or Dickie’s generational-money taste. Be it loungewear, crisply tailored suits or his signature jewelry, nothing feels out of place, or purposely excessive.

Enough so that, here now, a quarter-century on, Jude Law’s version of the character remains something of a cinematic fashion icon (as spoken too earlier this year by Vogue’s Radhika Seth).

But looks alone are never truly enough, are they? No, for it is how the story and characters are brought to life that is perhaps The Talented Mr. Ripley’s most enduring strength. An adaption that, though it may deviate from the source material on a 1:1 scale, still expertly captures the sinister spirit Highsmith was shooting for, with so much praise due to its relatively small but excellent cast.

Philip Seymour Hoffman made his career on the back of an indomitable energy and his turn in Ripley is no exception. As Freddie Miles, Dickie’s haughty, high-society friend, Hoffman dominates each scene in which he appears: an uncouth lout who, somewhat paradoxically, flaunts his standing at every opportunity.

He and Dickie may come from the same world (aimless, wealth-backed expatriates) but while the younger Greenleaf initially treats Ripley with an air of curious amusement, Freddie has no time for this lower-class usurper. His kinda-sorta playful banter thinly masking direct contempt that Hoffman clearly found great pleasure in bringing to life. It is a key but often overlooked dynamic that reaches its crescendo with the pairing of Minghella’s script and the duelling performances of Hoffman and Damon, following Dickie’s “disappearance”. Freddie, arriving unexpectedly in Rome looking for his friend, only to be greeted by Ripley instead. His suspicion, slowly turning to realization as he learns, too late, the mistake he has made, while having always seen through Ripley, in underestimating him.

Hoffman’s performance, succinctly then, is a standout, not just within the movie itself but the larger canon. A memorability that neither Billy Kearns could capture in the role in Purple Noon nor Eliot Sumner in 2024’s Ripley miniseries.

Elsewhere on the supporting side, while no other performer is given quite the same amount of material to work with, there are no true slouches, either.

As Peter-Smith Kingsley, Jack Davenport only takes on major prominence in the final act but he works wonderfully in contrast to Damon’s more closed-off, internally-at-odds depiction. Their emotional and later romantic relationship allowing Ripley to come the closet he ever has to a true human connection. Davenport, bringing such a warmth to his portrayal it then stings to see Ripley, in the film’s final moments, be forced to snuff it out, if only to protect his deceitful house of cards.

Cate Blanchett, in a film-exclusive role as vapid (but tremendously important) socialite Meredith Logue makes the most of her limited screen time, as does James Rebhorn as Herbert Greenleaf, while Philip Baker Hall cuts an imposing figure as Greenleaf’s private investigator, MacCarron.

Though the true heart of the film, whilst supported by this impressive foundation, lies within its trio of leads and above them, Minghella’s steady hand.

As Marge, Gwyneth Paltrow is given a series of layers and quite brilliantly, throughout the film, works to steadily peel them away.

We’re not given much of her background, no, ostensibly a socialite turned aspiring writer but also, someone who revels in the easy-going simplicity her life with Dickie provides. But such action, it doesn’t betray Marge’s interiority either. Despite knowing of Dickie’s inherent recklessness, from his serial infidelity or never-ending search for stability, Marge is firmly a woman in charge of her own course, even if it leads down a difficult path.

Paltrow, finding emotional resonance and agency within a character who, at a glance, would appear to lack them.

And at first, she sympathizes with Ripley, finding in him something of a kindred spirit. Be it his mostly fabricated stories of life in New York or the ebbs-and-flows during his earliest days in Mongibello, as he vies for Dickie’s ever-fleeting attention.

Yet in the aftermath of Dickie’s murder as Ripley works to protect his delicately-crafted illusions, Marge comes into clearer focus. Paltrow, delivering scene-after-scene of simply terrific acting, as the character struggles through heartbreak and then, deep suspicion, anger. No matter how carefully (or in some instances, hastily) he plots each move, either to throw off the Italian police or to cover his own tracks, Ripley finds himself unable to convince Marge, the only person to deduce the real truth (that Ripley killed Dickie and presumably, to her knowledge, Freddie as well), even if nobody believes her. A bittersweet conclusion to her arc, no doubt but it fits perfectly.

In the novel, Purple Noon and Ripley thrice, Marge comes to accept, to varying degrees, the purposed version of events (that Dickie either left her and/or committed suicide) but in doing so, it ultimately robs the character of a larger sense of individualism. Minghella clearly recognized this and Paltrow delivered on the most fully-formed version of the character yet depicted.

Though next to her, naturally, is Jude Law as Dickie Greenleaf, his, a presence so large, so grandiose, it dictates the movie wholesale from the very first title card to the close, long after he has physically left the screen.

And yet? Even with that understood, it seems Law’s casting wasn’t without uncertainty.

In a 2020 interview with Vanity Fair, by his own admission, he initially turned the down the role, fearing being typecast as a stock “pretty boy” just as his career was beginning to gain legitimate steam - only to reconsider upon seeing the caliber of creatives he would be partnering with.

And good thing, too.

As, from the moment he appears on screen, Law is utterly captivating as the junior Greenleaf, a charismatic, seemingly caring playboy who happily takes Ripley under his wing as something of a protégé. Sure, he has no wish to return to America and rightly so, as America comes with tedium and responsibility. Instead, he would rather spend his days drinking and sailing, his nights, in casual defiance of supposed loyalty to Marge, carousing jazz clubs with a hedonistic glee, each, blending into the next.

He relishes in being the centre-of-attention wherever he goes, whether it is as the faux-prince of Mongibello or the object of Marge and then Ripley’s immediately clear desire. The film’s broader, almost entirely unspoken thematic base doesn’t leave anything to the imagination, that is true but it is watching Law work within that framework that does.

As in, does he play, one way or other, into Ripley’s adoration from a place of faint flirtatiousness himself or simply as someone who knows nothing but the chase, whomever the pursuer? Law, depending on the moment, oscillates between these early on never giving any clear indication - his performance, existing in a grey area of sorts in which viewer interpretation is the only true metric: a challenging thing he makes look incredibly easy.

Though beneath this fun-loving façade is a man who is emotionally callous and deeply cruel. Immature and almost naïve to a fault, believing his never-earned wealth and self-obsessive societal respect will always shield him from consequence. Prone to outbursts of great violence with an explosive temper to match, this, a wrinkle that adds a great amount of colour to Law’s portrayal. A lingering danger all his own that comes to seal his fate once it becomes clear he has grown tired of and then, fatally, romantically rejects Ripley. Looking closely, one can see shades of Maurice Ronet in Purple Noon but Law doesn’t stay there long, making the role completely his own.

From taking Roth’s costuming choices and moving through each frame like he was born wearing Italian vintage or how even something as seemingly insignificant as the character’s posture informs deeper meaning.

Anyone who steps into Dickie Greenleaf’s orbit does so knowing, for better or worse, that he is the sun and they’re just along for the ride. And as Ripley assumes his identity (with no shade to Damon), he can only hope to match such aura.

The experience as a whole, is one Law continues to recall with fondness, even as his career expanded. He would be catapulted to fame following the movie - winning a BAFTA and being nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, while also becoming an immortal sex-symbol for the burgeoning Internet age.

Matt Damon’s Tom Ripley however, in contrast? He is a different beast all together.

To this point, when speaking to GQ in 2021, Damon openly acknowledged how he, Minghella and the larger team pushed themselves to expand and innovate creatively when considering the source material.

While the characters in Highsmith’s novels, including Tom Ripley can be very much “as presented” (specifically Ripley, being a sociopathic chameleon), in The Talented Mr. Ripley, there is a clear effort made to humanize him while, at the same time, not losing or overtly minimizing those character traits either. The wealth, the status, the respect, they are important to Ripley as he “becomes” Dickie yes but they are secondary to what he wants most - acceptance without conditions, to be loved fully for who he is, despite being unable to wholly reciprocate and recognize that himself.

Building off this then, is the verbally unspoken but clear expansion of the character’s sexuality.

Always left somewhat ambiguous in the novels and specifically so, in 2024’s miniseries, here, Ripley is very much a gay man, who, while aware of his presented veneer (especially so, during his interactions with Meredith) eventually comes to see complex emotions clashing with a “too-late-to-stop-now” energy. Even when he finds solace in his relationship with Peter during the final act, it comes with conditions only Ripley is aware of, that all-consuming drive, right to the very end, surpassing the small semblances of guilt and self-reflection he allows himself to express.

Damon, to great effect, buries much of this subtext under a carefully constructed mask he only allows to fall in certain moments. Never without intention or larger purpose, he and Minghella, drawing a thin line on which the character constantly walks. Could his murder of Dickie then, be considered a crime of passion, to some extent? Sure, as presented, it doesn’t come across as completely premeditated but to think that exclusively is to disregard the groundwork previously laid.

Ripley, plainly speaking to Dickie regarding his “three talents” (“Telling lies, forging signatures, impersonating practically anybody”) or how he carefully studies the heir’s idiosyncrasies. His handwriting, the specifics of his dress and physical mannerisms, building himself a reservoir on which to draw a life that seemed so unattainable, it wasn't even worth the dream.

Damon captures it all with such effectiveness, it is an interpretation of “young Ripley” that has come, now, to stand the test of time. 29 during the film’s production, there is a youthful boyishness he presents, one that courses side-by-side next to a dangerous undercurrent - that of a man who, as implied, has lived his entire life doing anything he could to survive. Alain Delon, at 25, had a beautiful unflappability in Purple Noon and Andrew Scott, well into his forties, brought forward a different approach all together in Ripley. But Damon, next to them, is an easy-to-point-to highlight, anchoring the film with ease. Already an established star post Good Will Hunting and Saving Private Ryan but not yet Matt Damon of Bourne and Oceans fame, one can believably buy him as a scrappy up-and-comer off the streets of Brooklyn.

Who, once he arrives in Italy, refuses to let go.

All that being equal though, the movie isn’t without some flaws.

For one, the pacing noticeably dips once the story moves to Venice, the concern over Ripley being discovered mitigated by the fact that he has already isolated his crimes from further examination so throughly.

It is only when Marge and MacCarron, to very different ends, begin looking to unearth secrets does that tension return, although such action bookends an extended cold stretch.

Depending on how much stock one places in a “faithful” adaption, the changes here may prove disappointing under that lens and while it deserves acknowledgment for its somewhat baseline LGBTQ2S+ representation, it shouldn’t be held up as the be-all, end-all in that space either.

But it endures.

Cool, supremely confident and bursting with style it is a movie of fantastic character. One that firmly closes its narrative loop, yet remains artistically powerful, from its performances, costuming and the sheer visual splendour it actively puts on display.

A movie built for a moment - that continues to live on.