Character-building is nothing if not a wildly imprecise science.

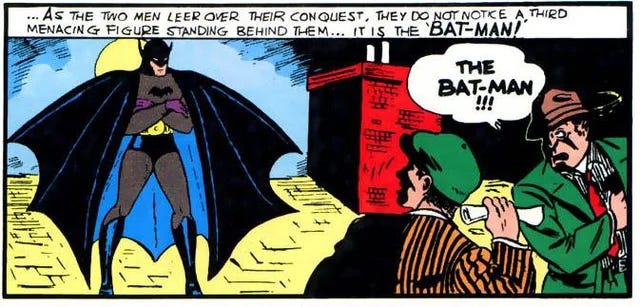

But it is fascinating to consider Batman in his debut, in the pages of Detective Comics #27, first published 85 years ago this weekend.

March 30, 1939.

In a case of murder and corporate conspiracy, police commissioner Jim Gordon finds himself crossing paths with a mysterious vigilante: “The Bat-Man”, the to-be-revealed alter-ego of supposedly carefree playboy, Bruce Wayne.

Gruff, coarse and with no qualms about killing criminals in his campaign against corruption (specifically, in this particular instance, by throwing them into vats of acid - and not for the first time either!).

So no, he wasn’t quite the “no guns, no killing” hero of yore he would one day become but the building-blocks, in essence, were there right from the start (unless you’re talking to Zack Snyder).

The motif, the code, the costume, right down to the pointy ears. A serious hero for a serious time with co-creators Bob Kane and Bill Finger, drawing on the contemporaneous pulp and noir characters of the period (Zorro mostly, with a dash of Sherlock Holmes, for good measure).1

But unlike his company predecessor in Superman, who debuted the previous year, Batman was not inspired by the belief of goodness in men. No, instead, he was driven to defeat the criminal element within them, whatever the cost.

Not a beacon of hope but rather, a dark symbol of justice.

The character quickly became a household name, a success that brought with it, a further sense of refinement. The initial imperfections would be ironed out (such as the establishment of the “no killing” rule) and his background, supporting cast and overall framework, now-iconic on their own, would develop rapidly following his introduction:

His base origin story would be revealed in Detective Comics #33 (November 1939). The eight decades since have seen various expansions and addendums to the overarching question of how he became the Batman (from comic storylines Batman: Year One to Batman: The Knight) but the fundamentals that everyone knows? They were first shown here. After his parents are killed in a mugging gone wrong, young billionaire-heir Bruce Wayne devotes his life to battling crime in (the yet-to-be-named) Gotham City, swearing at no one else will suffer the same fate, as he trains himself to his mental and physical peaks.

Detective Comics #38 (April 1940). Dick Grayson, the original Robin, debuts. After his parents are killed, Grayson, a young acrobat, is taken under Bruce Wayne’s wing and becomes his first and most well-known crime-fighting partner. He would stay in this role for the over thirty years. In the 1980s, however, he would become a hero all his own, adapting the identity of Nightwing to fight crime, solo, in the nearby city of Blüdhaven. He would remain a close ally to Batman, however as a member of the extended “Bat-Family”, even as others (Jason Todd, Tim Drake and Damien Wayne, most prominently) took up the Robin mantle in his stead.

Batman #1 (April 1940), featured the debuts of both Selina Kyle/Catwoman and Batman’s forever-archenemy, The Joker. While Selina would evolve over time - from villain, anti-hero and eventual love interest, The Joker, was always, well, The Joker. Originally introduced as a dangerous serial killer, his characterization would wear many hats over the years, depending on the era and creative team: from a wacky jokester to a sociopathic terrorist but his one true obsession, with The Batman, would remain a constant.

But nothing exists in a vacuum.

As America moved into the post-war years, Batman would undergo a shift, leaving his pulp roots behind, as more lighthearted, sci-fi-focused stories dominated the 1950s. A certain… zaniness, right? A thread that can followed, of course, right into the ‘60s, with the immortal campiness of the Adam West-led Batman TV series defining the character for a generation (you know, after all, some days you just can’t get rid of a bomb).

It would take the comics and the character as a whole, actual decades to shake that reputation, though - it was only in the 1980s, with the publishing of some of the character’s darkest and most memorable stories (most notably, 1986’s The Dark Knight Returns, 1988’s The Killing Joke and A Death in the Family) that returned Batman to a more grounded, realistic tone - something, that, more-or-less, has been the character’s MO for nearly 40 years now.

Although….the argument could be made that having such a tightly-held identity hasn’t been without its missteps, either.

Because unlike Superman (who hasn’t had a legitimately good movie since the 1970s) or his across-the-hall rival in Spider-Man, Batman, perhaps more than any other superhero, is deeply indebted to his adaptions, to the point that their influence has gone on to play important, critical roles in the source material.

Consider this: the introduction of The Batcave or the now-standard characterization of Alfred (by way of actor William Austin)?

They were both elements of 1943’s theatrical serial, Batman, the character’s first on-screen appearance - which quickly became comic staples (the serial though, on the other hand, plays deeply-problematic now with Batman and Robin presented as US government agents who espouse anti-Japanese sentiment).

It was something outside Batman media would and continues to struggle with, though - finding an effective balance between the material’s inherent ridiculousness (y’know, with the giant bat costume) and a tone, post ‘60s, that strove for a genuine sense of realism.

Tim Burton and Michael Keaton’s Batman films (1989’s Batman and 1992’s Batman Returns) were both dark sure but also blatantly fantastical, blending the revising the comics saw that decade with a sense of noir-styling that evoked those earliest adventures (including the Bat-sanctioned criminal murders!) but as the franchise grew without their involvement, it couldn’t escape the encroachment of camp, either.

And when I looked back on Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy last summer? I fought against this too - the realization that, more often than not, it is pretty clear that Nolan would have rather have been making straight-up action films over superhero fare.

Ultimately, it was Batman: The Animated Series (and its various spin-off and sequel projects) which remains the standard, particularly for the influence it still holds - from the revised, tragic origin for long-time antagonist Mister Freeze or the creation of Harleen Quinzel later, Harley Quinn, a former physiatrist turned-sidekick of The Joker.

In time, however, the character would strike out on her own, enough so that she is now a cultural staple in her own right, most prominently voiced by Kaley Cuoco in television’s Harley Quinn series, played by Margot Robbie on screen in the DCEU and later this year, by Lady Gaga in the second Joker film (in the comics? She is now a full-fledged, albeit repentant superhero, who works closely alongside the Bat-Family).

But in hindsight, much of the success brought forth by the animated series?

It was through the characterization done by its leads - the late Kevin Conroy as Bruce Wayne/Batman and Mark Hamill as The Joker. Conroy, expertly nailing the dark menace of Batman, without losing his humanity - something that seems simple on paper though it has been a point of contention in the live-action space since the beginning. And Hamill? Man. There is just something about his portrayal. Hitting all the expected notes - the whimsey, the cruelty, the inescapable darkness.

Their work, so good, so influential, it became the absolute gold standard for the characters for the better part of 30 years, as Conroy and Hamill reprised their roles together in countless other projects: from the acclaimed Batman: Arkham video games, various sequel series (Batman Beyond, notably) and animated films, up until Conroy’s death in 2022.

And yet.

Matt Reeves’ 2022 film, The Batman, may have ended on a note of optimism for Robert Pattison’s “it always rains in this Gotham” Batman and James Gunn’s separate cinematic version seems primed to be somewhat lighter but there is something inescapable that remains, even now, after 85 years - where exactly, do we, the reading and viewing audience, want Batman to land on the “goofy-noir” spectrum?

It isn’t a fixed question necessarily - but after Batman and Robin eroded the general audience’s trust in a lighter Batman, there has been, in my opinion, a transition too far in the other direction, at least from the mass media angle.

The comics, retreading too many of the same narrative beats, as they look to “deconstruct” Bruce Wayne and the movies (LEGO Batman being the obvious exception) far-too focused on the dark side of the character (Batman Begins, to be fair, found a good middle ground, although it wasn’t maintained going forward).

Batman, Robin, Batgirl. Catwoman, Harley and The Joker. The names alone are institutions in their own right and whatever they’re involved in? It’s going to make money - the question though, at least for me?

It is what the best approach creatively, should be.

To be Gotham’s Dark Knight? You shouldn’t always be bumbling around in the shadows, gargling marbles with hostility - if only to prove a point.

Bill Finger, like too many comic creators before and after him, would, unfortunately, have his key contributions to the character officially obscured for decades, with Kane being listed as Batman’s sole creator. Nearly 40 years after his death, in 2015, DC would finally rectify this, with Finger receiving proper credit since then: “Batman, created by Bob Kane with Bill Finger.”