While they weren’t necessarily scrappy upstarts in the traditional mold - so prized - having already found a measure of success as collaborators previously, as Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale went door-to-door throughout Hollywood the early 1980s, trying to get their newest project off the ground, it would seem, as Gale would later tell, that their luck had already run out.

Script rejections, numbering well into forties.

Executives, baffled by the candour present in their storytelling choices (particularly, whatever the hell they were doing with time-travel, in addition to that mother-son plot point).

Their comedy, paired with an honest emotional streak, disregarded. Being, as it was, more strictly sentimental than common denominator juvenile, per general custom at the time.

Undeterred, they persisted and with the backing of Steven Spielberg, production began on their co-written, Zemeckis-directed endeavour in earnest, in the late fall of 1984.1

No dice.

It still wouldn’t take.

For one, most prominently, it was clear that their chosen lead, Eric Stoltz, was not the man for the moment.

Maybe it was his hard, method-acting approach, plainly antithetical to the film they were trying to make. Maybe it was, as a byproduct, the difficult working relationships he cultivated with his co-stars and the larger production both.

Whatever the case, Stoltz, unceremoniously fired in January of 1985, was immediately replaced by a 23-year-old Michael J. Fox, who was, by their own admission, their first choice.

But for Fox, his overlapping commitments with Family Ties would mean that between sitcom filming and being hustled to the Universal lot, he would be coasting on only a couple hours of sleep a night, fuelled by little more than adrenaline and movie-making dreams.2

So, to take stock, it was to see Zemeckis and Gale, their proverbial creative car, throughly frozen by way of temporal displacement.

Battered with expectation.

Though having prepped, to an extent, for Stoltz’s departure, they were faced with the now-necessary reality of having sunk millions into footage that needed to be reshot wholesale, while being under the gun of an unforgiving window for their newly-minted and quickly exhausted star.

Weeks behind schedule, with promise in place of guarantees.

Here and now however, what is perhaps most impressive about revisiting Back to the Future, which released this week, in July of 1985, is that moment-to-moment, those production challenges, - though integral to the overall story - they aren’t even remotely visible.

It doesn’t feel as though it could have lost twenty minutes in editing. Needed cleaner exposition and dialogue, stronger character moments or more impactful performances.

No, instead, it is a film, so well realized in both vision and execution, it endures as a medium benchmark of remarkable quality, the best of the best, even if, it is, not totally bulletproof.

And so, here is Back to the Future: forty years later.

High-schooler Marty McFly (Michael J. Fox) is just trying to keep his head above water.

Spending most of his spare time with his girlfriend Jennifer (Claudia Wells), Marty tries to avoid his family, primarily father George (Crispin Glover) and mother Lorraine (Lea Thompson) whenever possible, for whom, despite his love, he finds he has little in common - particularly George, who is routinely bullied by his lifelong tormentor, the cruel Biff Tannen (Thomas F. Wilson).

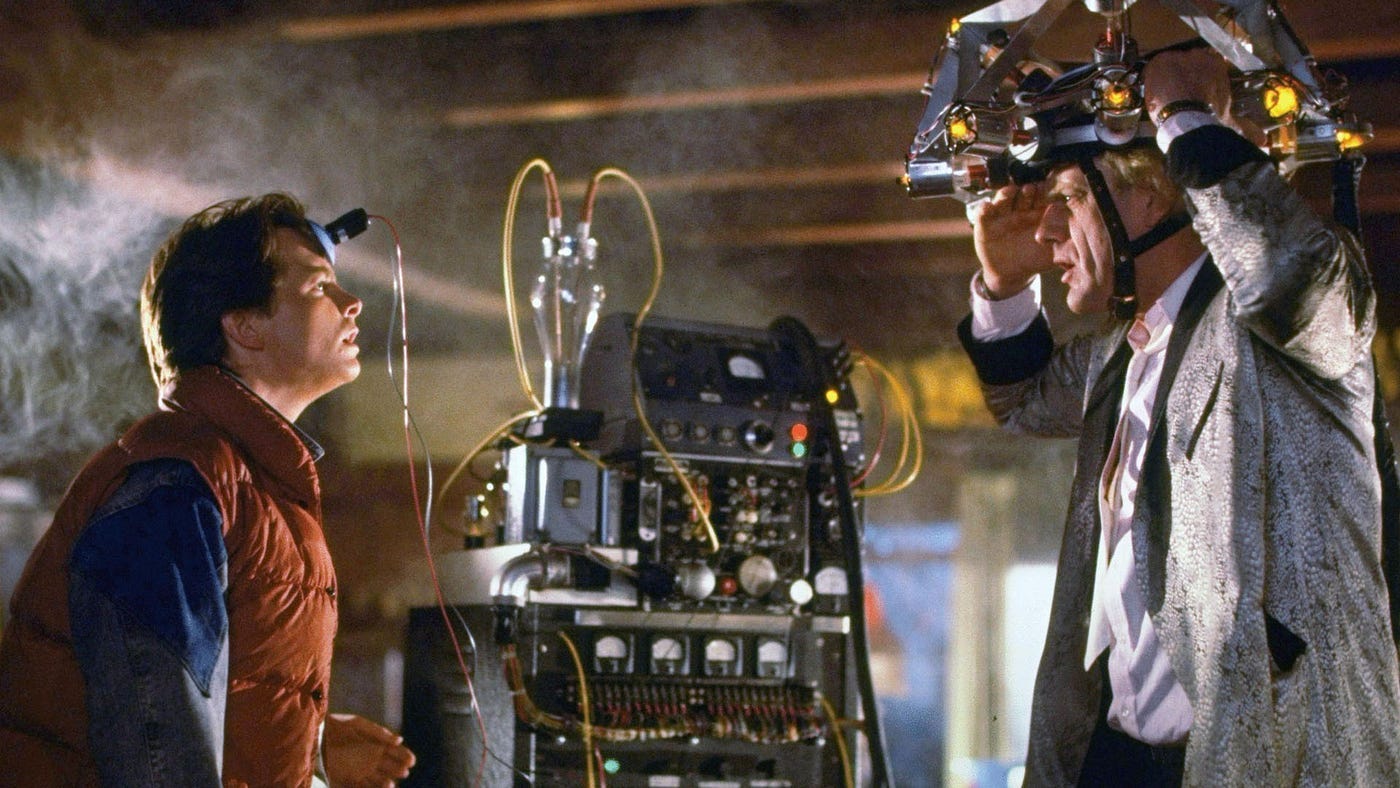

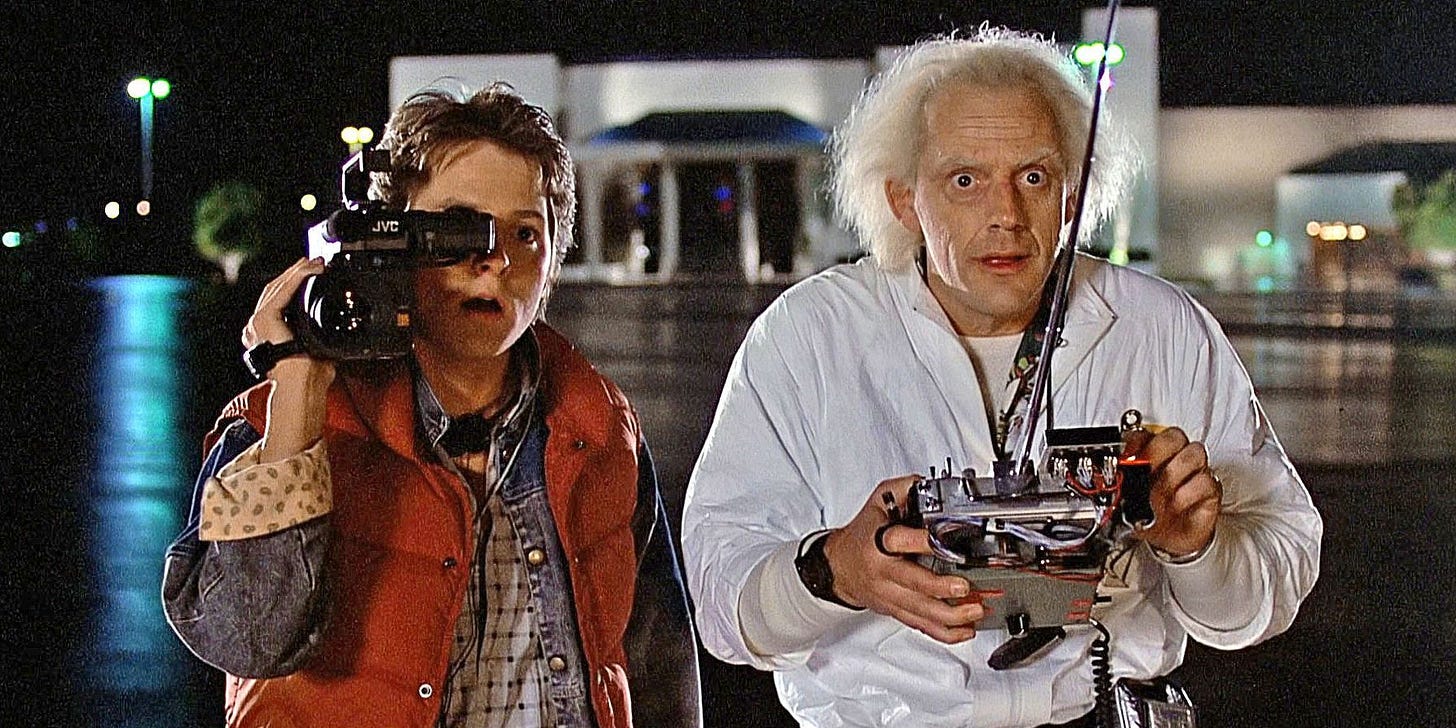

Though one night, Marty’s off-beat scientist friend, Emmett “Doc” Brown (Christopher Lloyd) shows him his latest invention: a heavily modified DeLorean sports car, which he has turned into a functioning time machine.

But when he accidentally travels thirty years into the past, to 1955, Marty soon realizes he has interfered with his parent’s first meeting, while also running afoul of a teenage Biff. With no other options, he enlists the help of a younger Doc where together, they begin planning to get Marty back home as simultaneously, Marty works to bring George and Lorraine together… to ensure his own existence before it is too late.

From a pure storytelling perspective, what continually works in BTTF’s favour is that virtually every plot point feeds into these parallel, intertwined stories.

Even the film’s one major subplot, Marty, with increasing urgency, trying to inform Doc of the full story of what occurred the night he travelled back in time, is itself dependant on the younger McFly actually returning to the 1980s in the first place. It doesn’t feel extraneous then, as though Zemeckis and Gale are lagging or artificially stretching their pacing to accommodate a larger story… it is the story.

This focus, allowing the film’s underlying tension to build organically, with a more strict character bent, even in the midst of its bigger set pieces.

The climatic clock tower sequence, for example, which remains a medium all-timer (tremendously stressful, even if knowing the end result), works in service to this idea, though with each additional, broader auxiliary piece being highlighted in support.

Alan Silvestri’s incredible score, the subtle but powerful special effects (which remain, overall, three cuts above even forty years later) or the general confidence that courses through every frame, outside of that immediate sphere.

Be it the visual storytelling in the contrasting period/then-contemporary set design or the lived-in, endless quotability of the dialogue, contributing to a world purposefully small in scope but feeling genuine all the same. There is the practical makeup work used for Glover, Thompson and Wilson in the opening act of the film, taking the three (then in their early through mid-20s) into middle age without being overbearing or the world-building wholesale.

From the comedic callbacks, to the opening tracking shot in Doc’s house, which tells the viewer, right away, everything they need to know about the character, a full twenty minutes before he even appears on the screen: the case of stolen plutonium, the over-eager inventions (with a focus on clocks/time, naturally) or the implied insurance fraud, shown via newspaper clippings of his family home, burnt to the ground. Said money, presumably used to fund his decades-long quest to build his time machine.

Speaking of, what of the DeLorean itself?

Almost instantaneously it became a movie prop held up in the highest esteem, ironic, in a way (if not because original drafts of the script had the machine be a nuclear-powered refrigerator) because the DeLorean Motor Company was already years-shuttered by 1985.3 John DeLorean himself, caught up in scandal and financial ruin before the film forever-elevated the stature of his much beleaguered vehicle, if somewhat tongue-in-cheek (from the general bewilderment towards the car or its most inopportune cold starts).

And yet, while each of those after-mentioned elements elevate the film in their own way, side-by-side, what remains perhaps its strongest factor is the most front-facing: its performers and the characters they inhabit.

Thomas F. Wilson is, purposely, totally utterly irredeemable as Biff but he brings an energy to his portrayal that isn’t once let up on. No humanity only rage, easily seeing him cement his spot in the ‘80s movie villain pantheon, of which competition is in no short supply. On the reverse, Crispin Glover plays George’s default timidness to effect, delivering a character believable in his presentation.

Talented but having been, it seems, put down and bullied at most every opportunity throughout his life, thereby, unknowingly, providing something of a window of reflection for his time-displaced son.

Lea Thompson doesn’t have as much material overall, in comparison but with great charm, she sells every scene in which she appears, the crux of which is easily the film’s most difficult and deliberately uncomfortable storyline, that, the dynamic between a teenage Lorraine and Marty.

Gale has acknowledged that this was one of the major hurdles he and Zemeckis faced when pitching the project, being flat out rejected on that basis alone before they struck a better balance, whilst maintaining the necessary degree of comedy.

Elsewhere, there are the movie’s few supporting, tertiary characters who, front-to-back, have very little screen-time but have become memorable all the same, be it James Tolkan as Mr. Strickland or Donald Fullilove as Goldie Wilson, his delivery alone, unforgettable.

But at the heart of not just the film but the entire franchise, is Christopher Lloyd as Doc and Fox, as Marty.

In of itself, it is a feat.

Almost any other film, well, any other storytelling undertaking, regardless of medium, it would be sure to establish its protagonists prior to their introduction. Hinting at backstory and previous adventures, even just sketching out the basics of how they met: though with Marty and Doc, not once does Back to the Future do this.

It is clear they have a strong pre-existing friendship, absolutely but the specifics of just how they got there are never explored.

Gale would, years later, eventually reveal some measure of it, mostly crystallizing what was already implied but the most amazing thing is the film, through the writing, through Lloyd and Fox with their top-notch chemistry, it doesn’t need this support.

Their character dynamic, it isn’t given a sheen of being inappropriate or open, really, to such mischaracterization in the first place.

Doc and Marty, they simply are. It is understood.

Marty is shown to have some external relationships of course, outside of his family, Jennifer, his bandmates, presumably but it is with Doc that he is most visibly at ease. Not entirely grasping everything he shares or says but holding an immediately apparent mutual respect, friends without question but for Marty, something of a father figure, as well, in contrast to his mostly empty relationship with George.

But it is on this base on which Fox’s performance builds from, Marty, coming into his own.

He is solid-on-his-feet yes, quick-witted, cool under pressure and though he spends most of the film on an emotional high-wire, as he tries desperately to get back home, to that end, it is show actual compassion towards George. Realizing that his own fear of rejection, it isn’t far off from what his father, as a younger man, once experienced, somewhat inadvertently imparting the wisdom that would see their futures forever changed.

Fox balances all these pieces so well, in what has become his career-defining role, he makes Marty fully endearing from the second he hooks up to the amplifier. Someone, perhaps, that speaks to the quintessential high-schooler in a what-could-have-been way, though not without a degree of relatable awkwardness, either

As Doc, Lloyd is tasked with playing two different but similar versions of the same character, a task he takes on with a relish.

1985 Doc, he is a little scattered to say the least, neatly filling the stock archetype the character was clearly built around but there is a confidence present too, hard-won from decades of trial-and-error which his 1955 counterpart lacks.

Unsure and doubtful, a scientist in name but having yet to fully see the fruits of his labour, that is, until he realizes his flux capacitor will indeed live up to its potential. While, at the same time, quickly realizing the importance of taking Marty under his wing, albeit, in the only way he can, through science.

It is a distinction he would further play up in the sequels but Lloyd brings an actionable enthusiasm to both versions of the character, in what became, like Fox, his most well-defined role. Doc, someone who has devoted his entire life to his profession, only to be reminded of the human element, specifically, by way of his as-seen, only friend, whatever the time period.

All-in-all, Back to the Future remains.

It is not removed from criticism by any means - the deeper implications of Marty riffing on Chuck Berry have never been great and continue to age poorly, alongside the deception of the Libyan terrorists or again, a fair measure of Lorraine’s story, notwithstanding Thompson’s portrayal - but it excels on so many of the fundamentals aside, its continued status as one of the greatest films ever made is assured, its cultural footprint, solidified.

Its two sequels would greatly expand on the scope and general mythology of the series, while pushing the barometer for special effects forward (Part II, specifically) and while highly enjoyable, fantastically-made films in their own right, both lack the honest simplicity of the original.

More produced, by design, than personable.

But even then, there is mystique that continues to surround the franchise, in this, The Franchise Age™.

Speaking earlier this year, Gale reconfirmed, once more, what he and Zemeckis have held by steadfast for decades now: there will be no fourth film, no reboot, no remake, no attempt to further capitalize on the series, beyond what has been agreed too under their tightly-curated control.

For of the few films that could truly stake a claim to indelibility, there is no doubt where Back to the Future lands.

Outtatime but ever-present.

Heavy.

Spielberg, having not-long-prior completed the transition from up-and-comer into major industry player himself.

And aren’t we all?

Of course, the nuclear fridge idea wouldn’t die then-and-there. Decades later, it would be, rather infamously, repurposed as a plot point in Spielberg’s Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull.